What do Franz Joseph and a woman revolutionary have in common?

For the one it was a matter of political conviction, for the other probably rather a source of pleasure, but it is unlikely that the two of them would ever have indulged in this vice together.

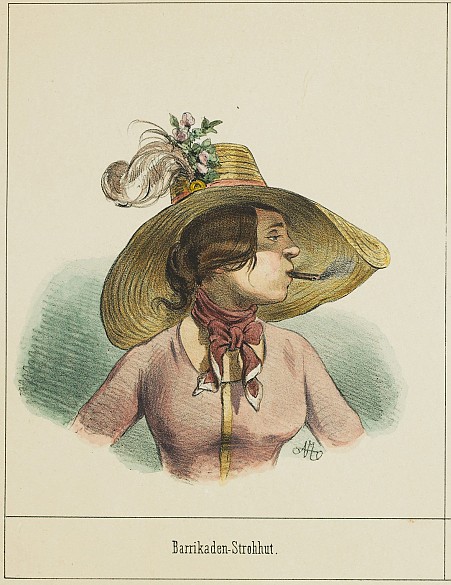

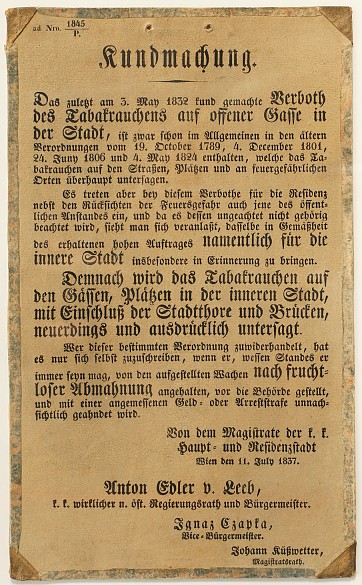

Franz Joseph was the first emperor to smoke. In the years before 1848 smoking was frowned upon at Court and people were forbidden to smoke, at least in public, smoking being seen as a fire hazard because timber was still widely used to build houses until well into the nineteenth century. This ban on smoking was, however, increasingly seen as a political imposition. For example, in 1831 a pamphlet proclaimed, ‘Unless smoking tobacco in the streets of the town is permitted forthwith there will be a revolution. The Imperial-Royal Lower Austrian Rebels.’ People who nevertheless smoked in public were considered dangerous trouble-makers and democrats. How smoking could indeed provoke a revolution was demonstrated in Vienna in 1846, when a brawl broke out between students and the police after the former had smoked in the street. One of the first ‘achievements’ of the revolution of 1848 was to have the smoking ban lifted – at least for men. Women were still subject to a social ‘smoking ban’. This led to tragedy for Archduchess Mathilde: she was burned to death in 1867 after she hid a cigarette under her clothes because she did not want to be caught smoking.

Besides, the state profited from the people’s taste for smoking, as in the nineteenth century up to twenty per cent of tax revenue came from its tobacco monopoly. The figure would have been even higher if there had not been a great deal of tobacco smuggling, which people indulged in more and more as a form of resistance against such impositions by the state.