On the edges of power – the four highest ceremonial Court ranks

The Obersthofmeister, Oberstkämmerer, Oberstmarschall and Oberststallmeister were the heads of the four Hofstäbe (Court staffs), the principal departments of the Court. Reserved to the senior nobility, they were the highest posts offered by the Habsburg Court. They symbolized hundreds of years of tradition, and on ceremonial occasions their holders comprised the immediate entourage of the monarch.

If one were called to one of these posts by the emperor, this meant a lifetime of personal service at the Court. This service only ended upon the decease of the monarch or the dignitary. It was not perceived as being an ordinary position of employment, but as a honorary service to the ruler, and yet it was remunerated with princely emoluments.

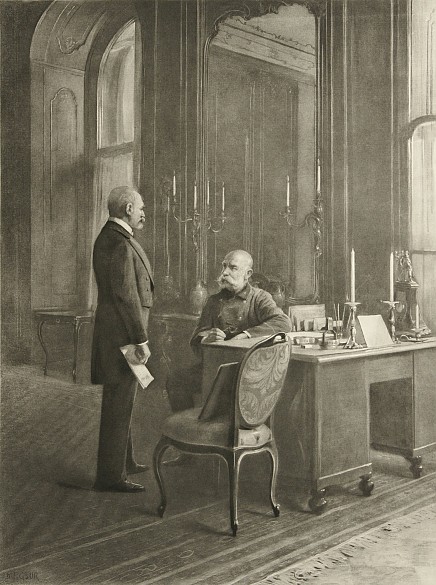

What were the advantages? Holders of the highest ceremonial ranks enjoyed preferential rights in terms of access to the monarch, for they formed the link between the Emperor and the Court. In order to safeguard the inaccessibility of the monarch, with which personal involvement in the procedures of court administration was incompatible, the Emperor issued orders via his dignitaries.

At the top was the Obersthofmeister, who held the top supervisory position over the entire court and was, in modern parlance, the managing director of Habsburg & Co. He had a very broad range of duties, being in charge of the Kanzleidirektion, the economic administrative centre of the Court and, attached to this, the so-called Court services, meaning the actual Court household; this covered the provision of food and accommodation to the Court as well as cleaning and heating the court buildings.

As head of the Court Household, he also had supreme command over the Court guards, who were responsible for the security of the monarch. His portfolio also covered management of the physical and spiritual wellbeing of the Habsburgs, plus the court clergy and medical staff, including the court pharmacy.

Ranking in second place was the Oberstkämmerer, the head of the imperial chamber, i.e. the monarch's private domain. He controlled access to the ruler and issued appointments for audiences. His sphere of influence also included the imperial collections.

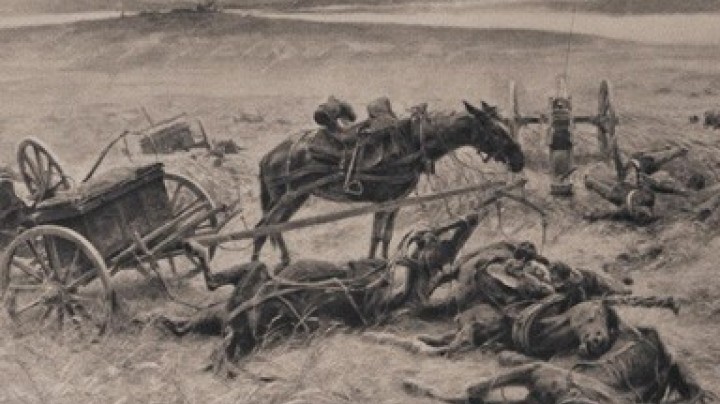

The Obersthofmarschall saw to law and order at the court. Originally, he actually exercised jurisdiction over the court servants, but by the nineteenth century his responsibilities had become reduced to legal matters within the Habsburg family. Particularly during the latter period of Franz Joseph's rule, this department had to deal with a number of racy scandals inside the highest house in the land.

Finally, the Oberststallmeister governed the court stables, the riding school and the Wagenburg, the fleet of court carriages and other forms of transport. Here it was not just a question of mobility, but also prestige; thoroughbred horses and magnificent equipages were a cornerstone of aristocratic display, and thus this department was very costly and required a large number of staff.