The Court as the source of power

The Court had its own rules of play: the nobility had to accept certain modes of conduct which the ruler could use as an instrument to keep them on a tight rein. Membership of Court society was nonetheless highly coveted, as the Court became the central hub for important information and prestigious positions.

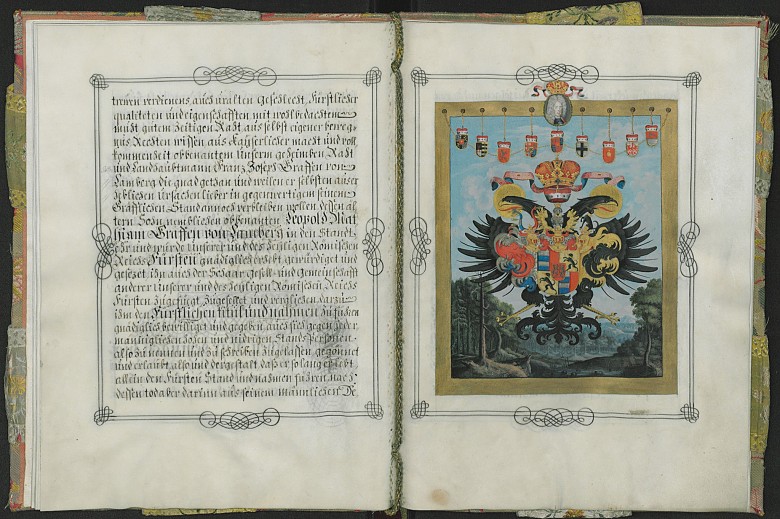

Thanks to the multi-layered nature of Habsburg dominion – as a rule Habsburg monarchs not only bore the title of Holy Roman Emperor but were also Kings of Bohemia and Hungary, Archdukes of Austria, and so on – which put an enormous concentration of power into the hands of the Habsburg rulers, the Viennese Court offered the politically loyal members of the nobility from the Austrian, Bohemian and Hungarian lands huge opportunities as regards careers and the acquisition of property.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the dynasty ultimately emerged victorious from the trial of strength that had been going on between the House of Habsburg and the provincial Estates for the distribution of power. His position now confirmed, the monarch could protect and support individual families by conferring privileges and elevations in rank. New prestigious ranks, even finer distinctions of title and new categories in the aristocratic hierarchy were created which the emperor alone had the power to bestow. Noble houses that had previously regarded themselves as being of equal rank now found themselves on different rungs of the hierarchy, and newcomers who had been granted exclusive titles by imperial favour were suddenly placed on an equal footing with or even given precedence over families from the old-established nobility. This set a kind of competition in motion, as the families affected now also had to strive to attract the emperor’s good will in order to keep their position in the sensitive hierarchy of the nobility. However, this strategy was only successful if one subjected oneself to the rules of play that obtained at Court – proud nobles were now forced to come to the Court and seek positions that secured them proximity to the emperor.

Thus the emergence of the Habsburg Monarchy can be seen as the successful social and political integration of the noble elites. A supranational higher aristocracy came into being for whom language and ethnic origins were of only secondary importance. What counted were equality of rank and position in the Court hierarchy. Although many nobles had estates in different provinces of the empire, they were united in a ‘Habsburg patriotism’ based on the Monarchy as a whole, bound by close ties to the dynasty and its ideological programme.