The Court Kitchens – dining at the emperor's behest

Franz Joseph was considered to have very modest demands; his personal taste in food was not particularly sophisticated, and his predilection for boiled beef (‘Tafelspitz’) is legendary. However, the court kitchens constituted a top-class gastronomic operation. A huge household had to be fed, for not only the emperor got hungry, but so did his staff.

The court kitchens comprised various kitchen areas for the preparation of meat, cold meals and pastry confections. The Hofzehrgaden (Court Depot of Victuals), which dealt with the purchasing and storage of food, the Hofzuckerbäckerei (Court Confectionery), which produced sweetmeats, hot drinks, soft drinks and frozen dishes, plus the Hofkeller (Court Cellars), were all separate departments.

The day began early; from five o'clock, over 500 portions were prepared for breakfast. At midday, it took two hours to distribute the food. Since there was no canteen, meals were eaten at one's place of work, even if this was just a quiet corner in a corridor of the Hofburg.

The portions were described as generous, for servants often shared their food with members of their family. Feeding all the court employees, who numbered over 2,000, was organized by way of a modest contribution at cost price, which was popular particularly among the lower ranks, though occasional instances of abuse did arise, when meals were sold on at a higher charge. There were three categories, with the difference lying not in the quality of the dishes but in their quantity. The most expensive level was the ‘Kaisermenü’, which was what the emperor himself ate at midday. The regular meal plan was dominated by traditional Viennese fare. Following the soup, the main course generally consisted of meat accompanied by a side dish, and then a pastry dessert. This was served with beer or wine, and in various qualities depending on the diner's rank. In the evening, staff ate cold dishes such as bread with cold cuts of sausage, butter and vegetables.

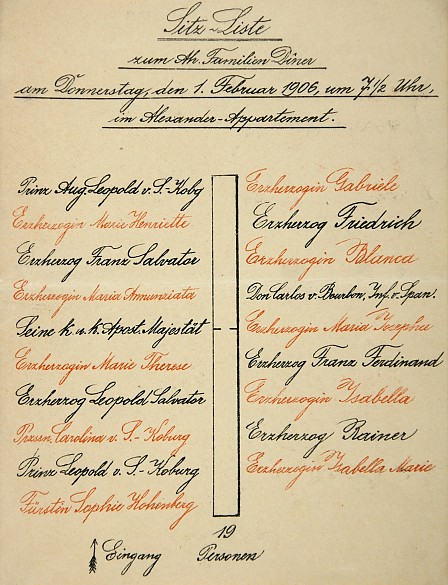

For Franz Joseph, supper varied depending on his schedule; if he did not have any official engagements he ate very modestly, and when staying at Ischl in the summer, he is said even to have contented himself with just fermented milk and dark rye bread. However, on special occasions, the court chefs had to prepare lavish menus comprising several courses. Three times a week, so-called Seriendiners were held, to which approximately 30 guests from public life were invited. On Sundays, family dinners took place, which all members of the imperial house who were present in Vienna were obliged to attend. Only illness was accepted as an excuse for not attending, and if need be, Franz Joseph even sent his own personal physician to check that he had not been deceived. However, when his closest and noblest relatives tried to avoid this obligatory appointment, it was not because of the poor quality of the food, but because family relations were far from idyllic ...