Trying out comfort and cosiness for a change: Biedermeier at Court

The new-style Viennese furniture was used to furnish the private apartments of the second son of Emperor Franz II (I) and his wife at Laxenburg – too modish in the opinion of Count Czernin, the acting head of the Court household.

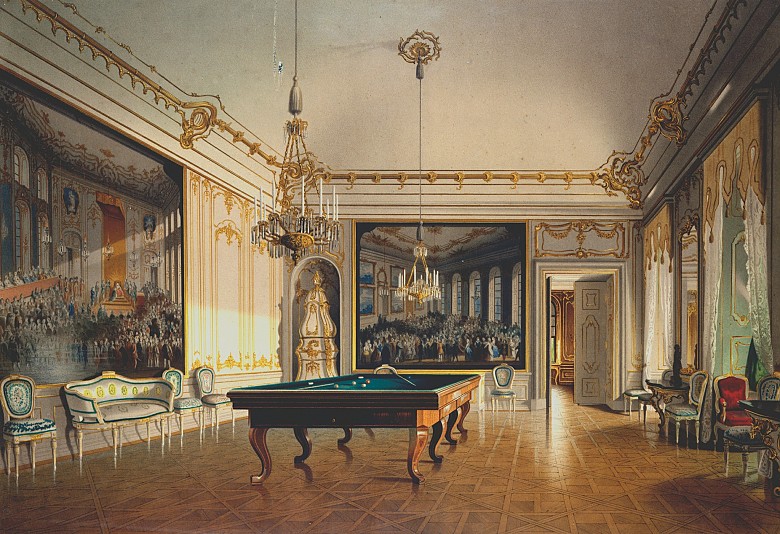

In 1825 the palace administration at Laxenburg was instructed to furnish and decorate apartments on the first floor of the Blauer Hof for Archduke Franz Karl and his wife Sophie of Bavaria. The archduchess’s suite was recorded in a series of watercolours by Johann Stephan Decker in 1826, and comprised a dressing room, a salon and music room, the marital bedroom, a drawing room-cum-study and rooms for the servants.

The apartments in the Blauer Hof at Laxenburg were furnished very plainly and modestly, in keeping with both the new fashion and the instructions given by Franz which decreed that the furnishing of apartments ‘in the country should be neither sumptuous nor expensive, but simply appropriate to decorum’. In 1828 the acting head of the Court household, Count Czernin, criticized the colour scheme of the rooms as too modish for an imperial suite.

Economy was the foremost concern in the furnishing of the apartments for the young archdukes in the Hofburg. These were to be furnished ‘with elegance and taste’, and the criteria for the children’s furniture were good materials and durability. New furniture was only rarely purchased during the reign of Franz II (I). Rooms were mostly furnished from existing stocks; little regard was paid to unity of style or modernity: in 1799 Court Furniture Inspector Caballini described the archducal apartments as ‘a hotch-potch’.

At the end of the eighteenth century a separation had taken place between the imperial residential suites and the state apartments. The residential apartments of the imperial couple and the archdukes then became independent private households within the imperial household system. They included rooms used for festivities and gatherings, music rooms and studies, billiard rooms, libraries and smaller rooms for staff. The same separation according to function took place in the palaces of the aristocracy and became a model to be emulated by middle-class households. Here, however limitations of space meant that it could not be implemented in the same way, and one and the same room was used for a variety of different functions.