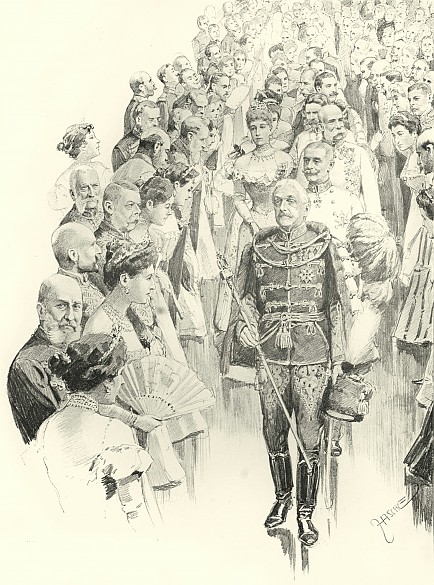

Members only – the right of admission to Court

Today equality is a fundamental human right. However, in feudal society, inequality was an immanent part of the system. The aristocratic elites at Court erected an insuperable barrier between themselves and the rest of humanity: the right of admission to Court – a birthright for which noble origin was the precondition.

Proof of noble birth was tested by special examiners in the office of the Oberstkämmerer (head chamberlain): in order to be accepted as a member of the ‘first tier of society’, the most exclusive aristocratic circle at Court, one had to produce proof of unbroken descent from at least sixteen aristocratic forebears – eight paternal and eight maternal ancestors. Not until the generation of one’s great-great-grandparents was a ‘lapse’ tolerated, that is, marriage to a partner from the lesser nobility or – horrible dictu – even from the middle classes. This explains the strict rules of marriage in aristocratic circles, as a morganatic marriage (that is, to someone of lesser birth) meant the loss of privileges for one’s descendants: whoever stepped out of line ruined the chances of subsequent generations.

At the Viennese Court the right of admission to court remained the most important instrument for preserving exclusivity until the end of the Monarchy in 1918. Under Franz Joseph, whose views were steeped in the traditions of the dynasty, people of middle-class origins were prohibited from becoming members of Court society. This was an archaism, as the aristocracy had largely forfeited its historic privileges outside the Court after 1848. The higher nobility, which now had to compete with the middle-class meritocracy, sought refuge in the past and was trapped in the cultivation of its traditions.

Few aristocrats criticized this state of affairs: Crown Prince Rudolf recognised the dangers of isolation and deliberately sought contact with middle-class citizens from academe and industry. Significantly, this conduct made Rudolf an outsider, not only within his own family but also in Vienna’s aristocratic society.

The nobility that thronged to the haven of the Court orbited the imperial dynasty like planets around the sun. With the decline of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918 the centre of gravitation and thus their point of reference was gone. The abolition of aristocratic titles and the loss of the privileges that went with them together with the massive financial losses sustained following the political developments in the individual successor states of the Monarchy brought the final curtain down on the world of Austria’s old aristocracy.