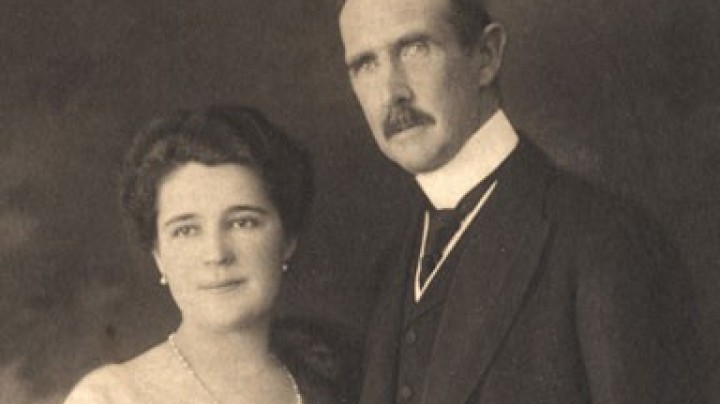

Marie Louise and the Duke of Reichstadt

Astonishing as it may seem, the marriage of Marie Louise to her father's archenemy, who was also 21 years older than herself, became a happy one. When Marie Louise gave birth to the much longed-for heir to the throne on 20th March 1811 in Paris, their joy seemed complete. But the dream of founding a new, powerful dynasty was not to be realised: only three years later Napoleon's luck in battle changed and he was overthrown.

Napoleon was attentive and tender to his young wife, and Marie Louise returned his affection. Nine months after the wedding the empress was delivered of a boy on 20 March 1811. The birth was so difficult that the attending physicians were faced with the decision of saving the life of the child or that of its mother. The distraught emperor asked them to save the mother, and when the child was delivered by forceps, it appeared lifeless. Joy was unbounded when the infant, which had been heedlessly laid on the carpet, began to show faint signs of life. The same day Napoleon invested his newborn son with the title of “King of Rome” – the title that ensured expectation of imperial dignity in the Holy Roman Empire. The child, for whom the father cared lovingly, was baptised Napoleon Franz.

Marie Louise quickly felt at home in Paris, adopting the French lifestyle and soon preferring to speak French rather than German. It was a heavy blow for her when she realised that her days in Paris were numbered after the fall of Napoleon. With conflicting emotions, she and her small son returned to her native country, where their fate depended on the victorious powers. As compensation Marie Louise was awarded the Duchy of Parma with Piacenza and Guastalla. As the court of Vienna knew how much it would upset Marie Louise, the many letters that Napoleon wrote to her from Elba were intercepted and concealed from her. In order to distract her thoughts, Emperor Franz I appointed Count Neipperg as her protector and advisor. After Napoleon’s death she married the count secretly, having already borne him two illegitimate children – a lapse that Emperor Franz forgave his daughter. After Neipperg’s death she embarked on a third marriage with Count Charles-Rene Bombelles. The former Empress of France ruled Parma with a wise hand, doing much good for her country. Her last words – “Addio amici miei” [Farewell, my friends] – were addressed to the representatives of the state council.

When Marie Louise left for Parma in 1816, her son remained in Vienna and grew up under the guardianship of his grandfather and the watchful eyes of Metternich. The little blue-eyed boy with his blond curls was soon a firm favourite with the court, exerting a strange but fascinating charm. In 1816 the title of Duke of Reichstadt was created for him. Marie Louise rarely visited Vienna but sent regular gifts to soothe her troubled conscience. The child pined for his mother and was beside himself with joy when she finally visited Vienna. Insecure and irresolute, Marie Louise did not dare assert herself against Metternich and take her child to Parma. When the “delicious Reichstadt”, as he was commonly known, became a young man, he was surrounded by female admirers of all ages who found him irresistible. His military career was constantly interrupted by illness; since early childhood he had suffered from chronic bronchitis and respiratory infections which were always accompanied by severe coughing spasms. In June 1832 his health deteriorated to such an extend that Marie Louise was summoned from Parma. When she eventually arrived at Schönbrunn after the long journey she found her son dying. Tuberculosis had destroyed his lungs and larynx. The once tall (1.86m/6 ft), handsome duke lay on his deathbed, reduced to mere skin and bones. Shortly before his death he whispered: “Oh God, mother of mine! I am done for!”