Archduke Johann: back to nature – the Tyrolean Garden at Schönbrunn

The Habsburgs had always had green fingers. Indeed, emperors and archdukes were not averse to picking up a spade or rake themselves in the garden from time to time. Some members of the illustrious house of Habsburg even liked to adopt the role of simple unsophisticated country folk.

The longing for ‘unadulterated nature’ in Romanticism was a reaction to industrialization and social change in the wake of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. A new perspective on nature arose; it was no longer seen as an enemy threatening humanity, but as an idyll.

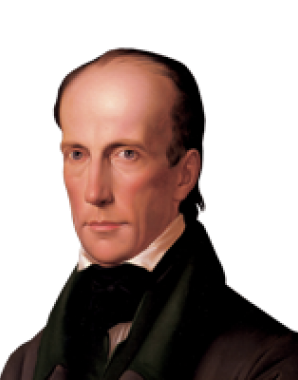

The elite, weary of civilization, now turned their focus to the Alps, where it was believed one could perceive true, unspoiled co-existence between Man and Nature. Archduke Johann in particular is famous to this day for his life-long association with the Austrian Alps and its inhabitants. It is thanks to him that members of the imperial house began taking pleasure in wearing traditional Alpine dress.

As an expression of how much he appreciated rural life, Johann had the Tirolerhof – a miniature farmhouse in traditional Tyrolean style – erected in the park at Schönbrunn. However, he did not just plan to graze Alpine dairy cattle there. A Senner (Alpine herdsman and dairyman), ‘hale and hearty ... of good moral demeanour, principally displaying utter loyalty and true Swiss spirit, in short, an Alpine shepherd’, who would blow his alpenhorn and wear regional costume, also served to fulfil the archducal aspiration for authenticity.

Less whimsical, but entirely fitting with the imperative of benefit to the general public, was the layout of the Tyrolean Garden, which consisted of medicinal herb gardens and kitchen gardens as well as plantations of fruit trees, the seeds and cuttings of which, produced through cultivation and grafting, were given free of charge to interested parties.

The Schönbrunn Tirolerhof no longer exists in its original form. In its place there stands today a replica operated by Schönbrunn Zoo as a restaurant, a ‘city farmhouse’ in the immediate vicinity of the Zoo, consisting of a historic Tyrolean farmstead transferred to Vienna especially for this purpose. Archduke Johann would most certainly have found pleasure in such an enterprise.