Rudolf II and the ‛Golden City’

The magic of Prague lies on the one hand in its historic architecture and on the other in the evidence of the coexistence of different ethnicities in the ‛Golden City’, as it is known in Czech and German. This fascination is embodied in the person of Rudolf II, at whose court an aesthetic parallel world was created that presented a bizarre discrepancy to the dwindling power of the emperor.

Rudolf’s contradictory personality has been variously described: as a strange melancholic, an enigmatic friend of the arts and sciences, even as a mentally disturbed fantasist and eccentric, caught up in a world of dreams.

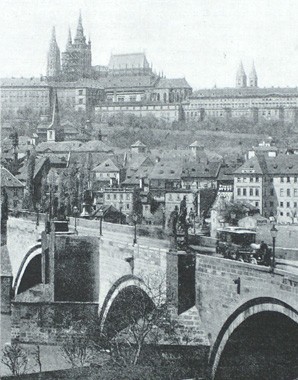

In 1583 he moved his court to Prague, at that time a much larger city than Vienna and one that was characterized by complex political and religious circumstances. The marked artistic predilections and scientific interests of this Habsburg soon gave rise to a dynamic artistic atmosphere and the proud imperial city became a magnet for international artists. In addition to painting, Rudolf had an especial predilection for the work of goldsmiths and gem-cutters. The imperial collection evolved into a cosmos of its own, ordered on aesthetic criteria, the opposite of the chaos of reality outside the walls of the Kunstkammer.

The emperor surrounded himself with a circle of scholars. Here, however, seen from a present-day perspective, the boundaries between science and superstition, scholarliness and charlatanism, were fluid. The figures at the Prague court included not only Tycho de Brahe and Johannes Kepler but also occultist adventurers who have left their traces in the legends of Prague.

One of these legends has been – spuriously – attached to the figure of Rabbi Löw, who supposedly used his magic powers to breathe life into a creature made of clay known as the Golem. The real Rabbi Löw was in fact a rigorously orthodox Talmudic scholar under whose auspices as Chief Rabbi the Jewish community in Prague grew to become one of the foremost in Europe. Rudolf, who was fascinated by occult matters, invited the learned scholar and mystic to a private audience at court.

The emperor increasingly suffered from psychological problems which expressed themselves in a retreat from the world accompanied by lethargy and depression and punctuated by outbreaks of rage and acts of self-destruction. Politically isolated and described as insane by his opponents, he made vain attempts to cling on to the remnants of his imperial authority. Forced into a corner, he was eventually deprived of his power by his brother Matthias in 1611 and died a year later. He was buried in the royal vault beneath St Vitus’ Cathedral in Prague Castle.

The huge imperial collections were dispersed after his death. Rudolf’s tragic fate became a piece of the romantic myth of ‛magic Prague’.