The Neugebäude – an idealist’s dream

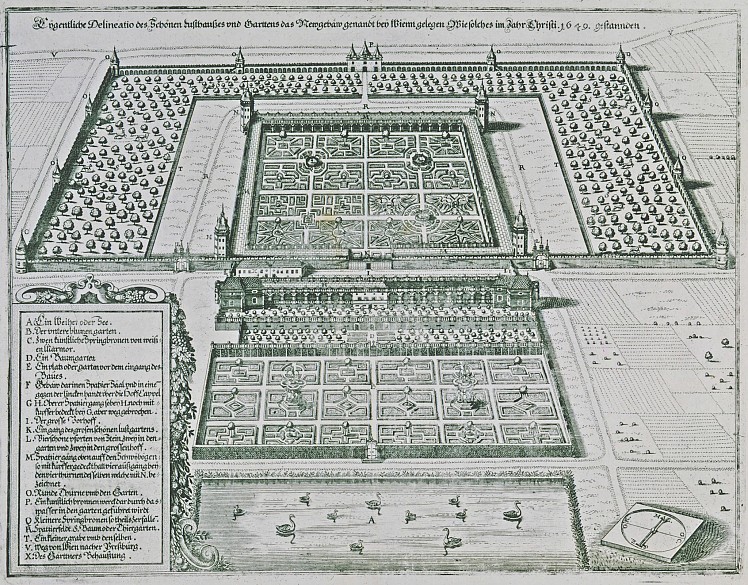

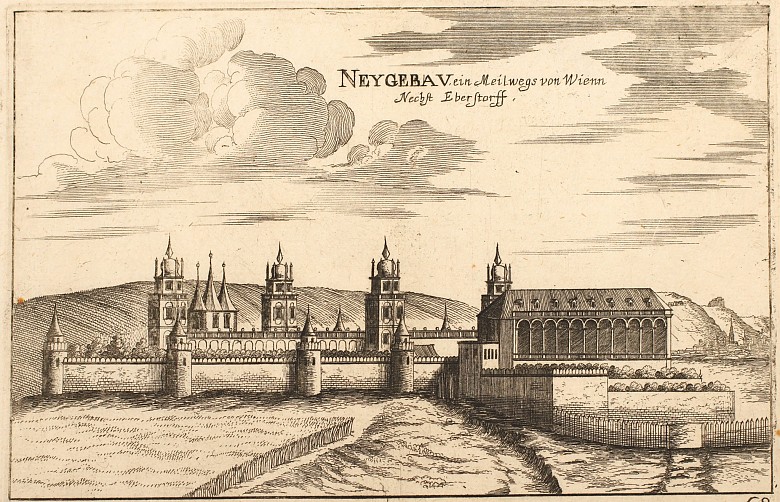

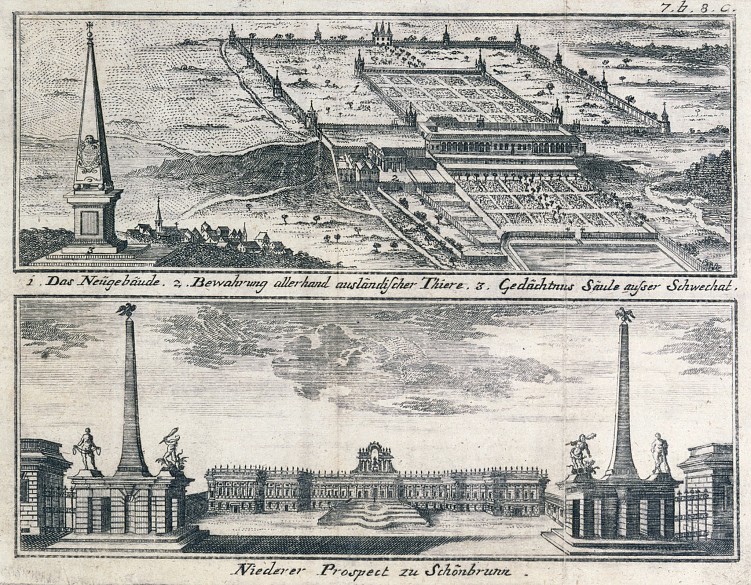

Today the Neugebäude is a largely forgotten palatial complex whose sparse remains have been swallowed up by the modern city of Vienna. An idea of its former magnificence can now only be obtained from old engravings: the torso of this Habsburg edifice stands symbolically for the vain attempt of the individual who commissioned it to realize his ideal of a world of culture and art.

Emperor Maximilian II was seen as a conciliatory character who attempted to rise above the strife between Catholics and Protestants. His personal tolerance and abhorrence of religious extremism often left him on the opposite side of the fence to his Spanish relatives with their uncompromising Catholic stance.

A cultivated humanist, Maximilian sought to realize the ideal of artistic and scientific universalism at his court. He laid the foundations of the imperial collections and gathered around him a circle of humanists and cosmopolitans. Maximilian’s universalist approach is also reflected in the underlying conception of the Neugebäude, which was intended as a place of encounter with treasures of art and Nature, an image of the world in miniature.

The palace was designed as a Gesamtkunstwerk on the model of the Roman imperial villas: its location on the broad expanse of the Simmeringer Haide outside the confines of the largely medieval city of Vienna was in keeping with the humanist ideal of recreation in rural surroundings – an aspect that is today hard to imagine, given the present-day situation of the site in the heavily industrialized southern fringes of the Austrian capital.

The main building, which was to house Maximilian’s collections, sat on the edge of a terrain with sweeping views of the wetland forests along the Danube. Between the latter and the gardens was a fenced-in game reserve, forming the transition to open countryside. Immediately surrounding the palace was a pleasance with fountains, grottoes and arcaded walkways where rarities such as tulips, lilac and the potato plant grew and exotic animals – brought to Vienna to satisfy the emperor’s scientific curiosity – could be marvelled at.

Work started on the palace in 1568, but it was still unfinished when Maximilian died suddenly in 1576, and the following generations of Habsburgs showed little interest in completing it. Under Maria Theresa the decaying complex came to the end of its existence as an imperial château de plaisance: she gave orders for the usable architectural elements to be recycled for the building of the Gloriette at Schönbrunn. The Neugebäude was handed over to the army for military purposes and used as a powder magazine. In the 1920s parts of the grounds were used to build the crematorium for Vienna’s Central Municipal Cemetery, and the palace itself, half-ruined, still awaits a suitable use.