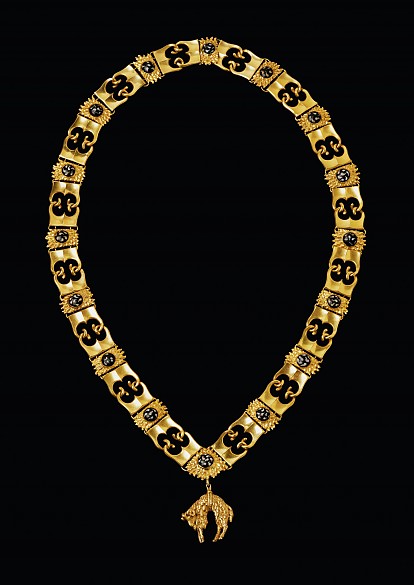

The Golden Fleece

The Order of the Golden Fleece was the ‘badge’ of the Casa d’Austria, its various symbols part of the fundamental accoutrements of all male Habsburgs in official portraits. A mysterious aura surrounds the archaic rituals and statutes of the Habsburg family Order which have existed essentially unchanged since its foundation more than 500 years ago.

To be admitted to the Order, candidates must be males of noble birth and baptized in the Roman Catholic faith. The Order is limited to fifty members. The head of the Order, that is, the head of the Habsburg family, decides on who is to be admitted. The knights of the Order still assemble on the day of the patron saint of the Order, the Apostle St Andrew (30 November) for their Chapter meetings.

The Order originated at the magnificent court of the Dukes of Burgundy, where it was founded in Bruges in 1430 with the intention of renewing the idea of the miles christianus (Christian soldier): infused with ideas from Christian theology and classical mythology, it sought to combine the honour of Western chivalry with the defence of the Christian faith. Its noble members were bound by ties of personal loyalty to the sovereign, but also constituted as it were the moral conscience of the monarch.

As part of the Burgundian inheritance brought by Mary of Burgundy when she married Maximilian I in 1477, the Order was a welcome instrument to the ambitious Habsburgs to strengthen the bonds holding together their inhomogeneous dominions by admitting the aristocratic elites of the individual territories to the Order. Under Charles V and Phillip II, the Golden Fleece became the expression of uncompromising loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church, a bastion of Habsburg ideology and a bond between the two branches of the lineage.

After the Spanish line had died out in 1700 the Habsburgs lost the Spanish crown, but their sovereignty over the Austrian Netherlands, where the Order had originated, gave them the legitimate basis for heading it. The symbolic language of the Order was of enormous importance for the Habsburg during the Baroque era in particular, as it served as the ideological foundation for imperial claims to universal dominion and also to stylize the wars against the Turks as the defence of Christendom. Among the Austrian elites, membership of the Order was regarded as the zenith of a career, as it secured absolute precedence in the courtly hierarchy.

After the decline of the universal principle of monarchy in the wake of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, the reactionary and anti-modern character of the Order intensified: the Golden Fleece became a glittering accoutrement from the great past of a venerable dynasty.