No queen without a throne – Maria Theresa’s accession

The beginning of the reign of a new king or queen is traditionally marked with a coronation. The ceremonial festivities surrounding the ascension of the throne were followed keenly by ambassadors, commentators, the court household and the common people. This was all the more true of the coronations held for the only female sovereign ruler in the House of Habsburg.

Steeped in tradition, historical coronations are highly complex and symbolically charged ceremonies. Very few contemporaries had a true understanding of all their numerous aspects. This was a significant characteristic of coronation ceremonies: in their solemn and mystical rituals they conveyed the divine dimensions of the monarchy, whose mysteries would always remain beyond the ken of the ordinary subject.

Nonetheless, coronations sent out symbolic messages that were intuitively understood by observers from all social strata: the acts of anointing and crowning made of a certain individual a monarch chosen by God; by grasping the sceptre he assumed rulership of the realm, and the permanence and lawfulness of his rule was made manifest when he took his place on the throne.

All these messages had an overproportionate significance in the case of Maria Theresa, the first – and only – female ruler of the Austrian lands. The start of her rule was marked by the ceremony of hereditary homage (the swearing of fealty to the monarch) in Vienna by the Estates of Lower Austria just thirty-three days after her father’s death in November 1740. Never before had this ceremony for the new ruler of the Austrian lands been held with such haste; it created a fait accompli, silencing critics of the female succession.

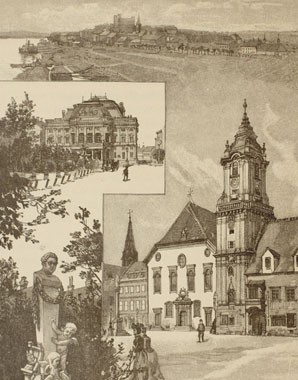

Maria Theresa’s coronation as ‘king’ in Hungary, the sovereign kingdom within the complex of Habsburg dominions, bore special significance. Maria Theresa was crowned according to the same procedure as her male predecessors and was addressed as ‘rex’ (‘king’) during the ceremony. With this, she conveyed to commentators and observers both at home and abroad that she possessed the same rights, privileges and power of rulership as a male king. She proudly wore the Hungarian crown – traditionally only held over the shoulders of queen consorts – on her head.

However, the traditional coronation ceremonial had to be adjusted for reasons of propriety. Because she was expecting a child at the time, Maria Theresa was unable to ride in the procession through Vienna and was instead carried in a sedan chair. And at the traditional mounted ceremony at the Coronation Mound in Pressburg, during which she brandished the coronation sword in all four cardinal directions as a sign of her willingness to defend the kingdom against its foes, she rode side-saddle. Nonetheless, this did little to weaken the message of strength that she was seeking to send forth. It was clear that Maria Theresa’s sex was not going to constitute an impediment to her exercise of power.