Failure and frustration

It was not only in public life that his problematic position prevented Rudolf from leading a life according to his ideals. He also felt he was misunderstood within the family and received little support from those around him.

Rudolf in a letter to his former tutor and fatherly friend, Count Latour.I can see the slope upon which we are sliding downwards, am very close to things but cannot do anything, am not even allowed to open my mouth to say what I feel and think.

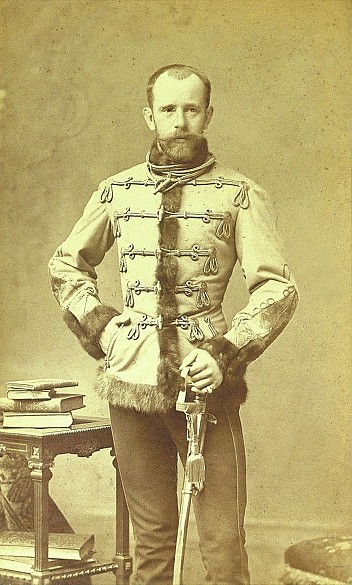

All his life Rudolf tried to gain his father’s recognition, but was systematically excluded by the emperor from all decision-making processes. Rudolf met with nothing but lack of understanding from his father, who expected his son to submit to his will and to function perfectly but was incapable of making his son feel appreciated. Franz Joseph completely ignored the suggestions Rudolf made for solutions to the political and social problems of the Monarchy, excluding him from any position of influence.

Rudolf also had a very ambivalent relationship with his mother. Although Rudolf had inherited many traits from his mother and both held similarly liberal views on many issues, a certain distance always remained between them.

In addition there were the problems in his marriage with Stephanie of Belgium, which had been imposed upon him for political reasons. It is telling that Rudolf travelled to Brussels to woo his bride in the company of one of his mistresses, which resulted in a huge scandal. Nonetheless, the arranged marriage initially seemed harmonious. Later however the couple developed almost diametrically opposed lifestyles. Stephanie was devoted to the traditions of the Viennese court and set great store by the privileges of her station. Rudolf on the other hand began increasingly to despise convention, escaping into numerous affairs and visiting prostitutes. He developed a predilection for the amusements of the ‘simple people’ and loved the carefree atmosphere of Viennese suburban taverns, which he visited more or less incognito. He was especially fond of Schrammel music and the taverns in the vineyards surrounding Vienna.

In 1883 the only child of this union was born. The little girl was baptized Elisabeth in honour of her grandmother. Called Erzsi in the family, the princess resembled her father and would later be notorious for her equally unconventional lifestyle. No further children could be expected, as Rudolf had infected his wife with a venereal disease, making her infertile and further worsening the relationship between them. The unhappy marriage became a disastrous situation for both parties.

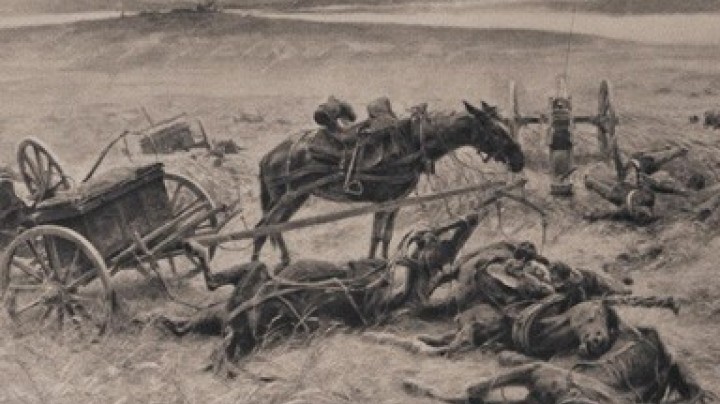

Frustrated by his isolated position in the family and at court, Rudolf sought release in alcohol and drugs. He suffered from depression, and his state of health was worsened rapidly by his lifestyle and the consequences of a venereal disease (probably gonorrhoea). The 31-year-old crown prince saw suicide as his only way out. Having toyed with the idea for some time, he found in his 17-year-old mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera, a companion who was prepared to die with him. On 30 January 1889 he put an end to his life by shooting himself. What actually happened at Mayerling has never been completely explained, not least due to the attempts of the Viennese court to obscure the true facts of the case. Among the majority of historians who have researched the subject, the most probable scenario is thought to be that Rudolf first shot his companion (with her consent), before killing himself. The tragedy of Mayerling ended the life of one of the most conflicted characters of the dynasty, and many regard it as marking the beginning of the end of the House of Habsburg.