Working at Court I: pro and contra

Freedom versus dependency, creative environment versus monotonous commissions – the advantages and disadvantages of a position at court.

Positions at court were a matter of controversy in artists’ circles: on the one hand they offered security and the freedom to work, on the other they involved being dependent on a lord, and it was not unknown for some princes to fail to pay their wages. The demands made on their artistic talents also varied greatly: the urban public wanted art based on existing traditions, while the courts were interested in new and innovative art as a way of distinguishing themselves.

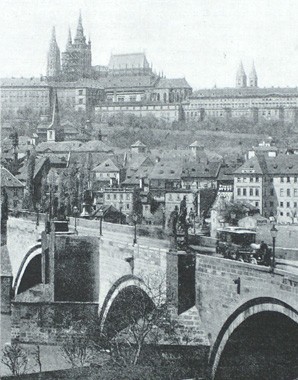

The courts of the early modern age offered a cosmopolitan environment and the opportunity of exchange between artists from all over Europe. At his court in Prague, Rudolf II, for example, employed lapidaries and jewellers from Italy, goldsmiths from the Netherlands and painters from Flanders and Germany. A particularly attractive privilege was afforded by employment at court in that it exempted artists from guild regulations.

The duties of a court artist were not limited to making art objects. They were also responsible for staging festivities, weddings and processions, and entrusted with the decoration of churches, for example with altarpieces. Churches represented one of the rare opportunities that the common people had of setting eyes on works by court artists. The majority of these commissions served to display the wealth and status of the court – portraits, engravings and sculptures of the ruler that emphasized his virtues and magnificence.

A position at court naturally enhanced the prestige of the artist – royal interest increased the value of the work. Some artists were even nobilitated, giving an enormous boost to their social status. Rudolf II ennobled Arcimboldo, Spranger and von Aachen. While this ennoblement could not cancel out their humble artisan origins, it did pay tribute to their work and achievements. In particular for the artists who travelled on diplomatic missions, it also facilitated access to princely patrons.