The pillars of Maria Theresa’s throne

Maria Theresa is regarded as a great ruler. However, as ruling is no one-woman job, she had the powerful support of numerous collaborators.

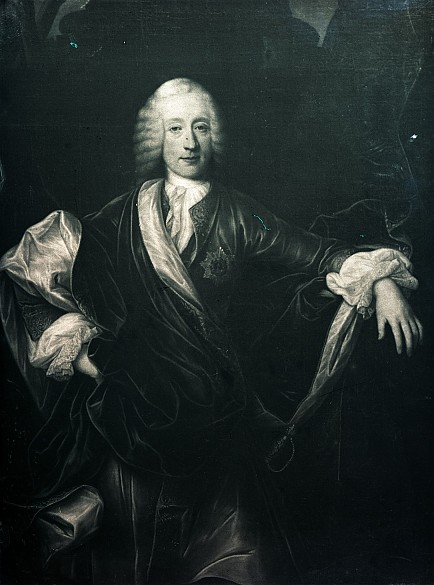

The Prussian ambassador Christoph Heinrich von Ammon in 1756 on Prince Wenzel Anton Kaunitz-RietbergWhen one first sets eyes upon him, Count Kaunitz gives the impression of being a cold man whose only concern is with his appearance and with worries about his health. And these matters are indeed those that concern him the most: he shudders at the slightest draught and only a little too much warmth gives him nervous attacks ... He has the weakness of not being able to pass a mirror without stopping in front of it – if only he dared, he would probably use rouge and beauty patches.

On the monument to Maria Theresa between the two great museums on the Ring in Vienna, her most important collaborators and contemporaries are grouped around the ruler as ‘pillars of the throne’. Composers such as Mozart and Haydn and military commanders such as Daun and Laudon are joined by four other men who were particularly influential in the reforms of Maria Theresa and her successors.

Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, who was a native of Silesia, is associated most closely with Maria Theresa’s early reforms, which he first tried out in Carinthia and Carniola. After the War of the Austrian Succession he was entrusted with the task of restoring Austria’s ruinous finances to good order. He played such an important role that Maria Theresa regarded him as a gift of providence. For eleven years, Haugwitz was president of the Directorate for Public and Financial Affairs (Directorium in publicis et cameralibus) and thus the most powerful man in the state. After being overthrown by his opponents in 1760, he became minister of state for internal affairs in the newly created Council of State (Staatsrat), where, however, he subsequently lost the upper hand to Prince Kaunitz.

Prince Wenzel Anton Kaunitz-Rietberg was to become Maria Theresa’s most important advisor in foreign matters. As he saw Prussia as the principal foe, he sought a rapprochement with Austria’s traditional arch-enemy, France, which led to their alliance in the Seven Years’ War. In 1760 he was responsible for the dissolution of the Directorium and the overthrow of Haugwitz. As Chancellor (Staatskanzler) from 1753 to 1792 Kaunitz was the most important advisor to three successive rulers: Maria Theresa, Joseph II and Leopold II. He dominated the field of foreign affairs but was also worked for the implementation of Enlightenment ideas in internal reforms.

In 1763, the lawyer and Freemason Baron Joseph von Sonnenfels became Vienna’s first university professor of police and economic affairs. He became particularly active under Joseph II and worked intensively for the abolition of torture. He was also editor of the Enlightenment weekly Der Mann ohne Vorteil (‘The Man without Prejudice’) and played an important part in the field of literature, being involved in the foundation of the Burgtheater in Vienna and campaigning against popular theatrical performances such those starring the much-loved figure of ‘Hanswurst’.

The Dutchman Gerard van Swieten studied under the famous physician Herman Boerhaave in Leiden before coming to Vienna in 1745 as Maria Theresa’s personal physician. As director of the court library he provided it with a reading room that was accessible to the general public. He reformed the university and brought a number of important figures from the world of medicine to Vienna, who founded the ‘First Viennese Medical School’. In addition improving the hospitals and sanatoriums, van Swieten was also behind the university being given a building of its own, which today houses the Austrian Academy of Sciences. As a protagonist of the Enlightenment he took a committed part in the fight against the widespread phenomenon of superstition, particularly with regard to the vampire myth, thus becoming the model for the vampire-hunter Van Helsing in Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula.