The people versus the useful emperor

Joseph II’s subjects were not always greatly enamoured with his ‘useful’ measures – which resulted in uprisings in Hungary, the Netherlands and elsewhere.

Joseph II to his friend Prince Charles de LigneYour land killed me. The loss of Ghent was my agony, the withdrawal from Brussels my death.

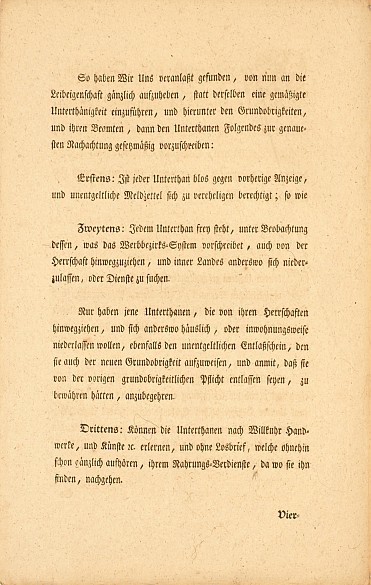

In 1784, 20,000 serfs gave loud expression to their dissatisfaction with the Hungarian landowners. The centre of this peasant uprising was Zlatna/Kleinschlatten in Transylvania. However, the ringleaders were betrayed and then cruelly executed in February 1785. Two thousand fellow peasants were compelled to look on as they had their arms and legs crushed and were finally disembowelled. Joseph II, who on account of not having bothered with a Hungarian coronation was known as the ‘hatted king’, had definitely come down on the side of those in power. Nevertheless, the insurgents did achieve a certain measure of success, as the same year saw serfdom abolished in Transylvania.

The end of the War of the Spanish Succession had seen the Spanish Netherlands falling to the Habsburgs, whose first governor there was none other than Prince Eugene of Savoy. Having failed in his attempts to exchange the Netherlands for Bavaria, Joseph II tried his hand at centralizing the administrative and legal system – in a territory where absolutist government had already provoked strong resistance. From 1 December 1786 there was an uprising in Leuven, which soon spread to Brabant. The governor Albert of Saxe-Teschen and his wife Marie Christine revoked Joseph’s decrees and were acclaimed for having done so.

The resistance was given support by agents of Prussia and spread further from July 1789. Having suffered the loss of Ghent, Flanders and the province of Hainaut, Habsburg rule was on the point of breaking down entirely. Spurred on by the French Revolution, on 11 January 1790 the rebellious provinces proclaimed that they had joined together to form the Etats belgiques unis (United Belgian States) and drew up a constitution.

After Joseph’s death, a return to the status quo was negotiated by his successor Leopold, who had already been critical of his brother’s policy in the Netherlands. In December 1790 the land was once again under Habsburg control and the rebels were granted amnesties. However, the outbreak of the War of the First Coalition against France soon led to the end of Habsburg rule in the Netherlands. On 6 November 1792, Albert of Saxe-Teschen was defeated at the battle of Jemappes by the French, who rapidly conquered the whole country as far as the Maas – the first of many Habsburg territorial losses in the wars that followed. At the Congress of Vienna, the Habsburgs no longer laid claim to the Netherlands, but the land was used as an important object of exchange for other territories.