Joseph II as co-regent

Following the sudden death of her husband Franz Stephan of Lorraine in 1765 Maria Theresa appointed her son co-regent. The fifteen years of their joint regency were overshadowed by the complicated relationship between mother and son.

In 1764, while his father was still alive, the crown prince had been elected his father’s successor in Frankfurt and crowned King of the Romans. Having made reason and rationality his guiding principles in life, Joseph saw himself as an alien body in the archaic etiquette of the coronation ceremonies.

The joint regency of mother and son in the years 1765 to 1780 represented a singular constellation that was without precedent at the Viennese court. As a widow, Maria Theresa continued to rule over the Habsburg Monarchy. Although she had initially announced that she wanted to withdraw from the world after the death of her husband, an event which affected her deeply, she soon changed her mind.

Joseph was Holy Roman Emperor, but by that time this was merely an honorific title conferring little authority to wield power. In the Habsburg dominions, however, he was – much to his regret – only co-regent, that is, a ‘junior partner’ of his mother, who kept the reins of power firmly in her own hands.

Constant differences of opinion made their collaboration extremely difficult and at times impossible. A generational conflict was here made worse by the collision of two formidable characters: a dominant mother confronting her ambitious son. The years of the co-regency were marked by a succession of clashes and reconciliations – more than once Joseph offered his demission, which Maria Theresa refused to accept.

As co-regent Joseph’s hands were tied. Maria Theresa put the brakes on her son’s reformist zeal, fearing it would endanger her laboriously established rule over her diverse dominions. Her outlook increasingly coloured by an all-pervading pessimism, the ageing dowager empress had lost the energy she had displayed in the initial years of her reign. She saw her role as the preserver of the status quo and was strictly against precipitate changes.

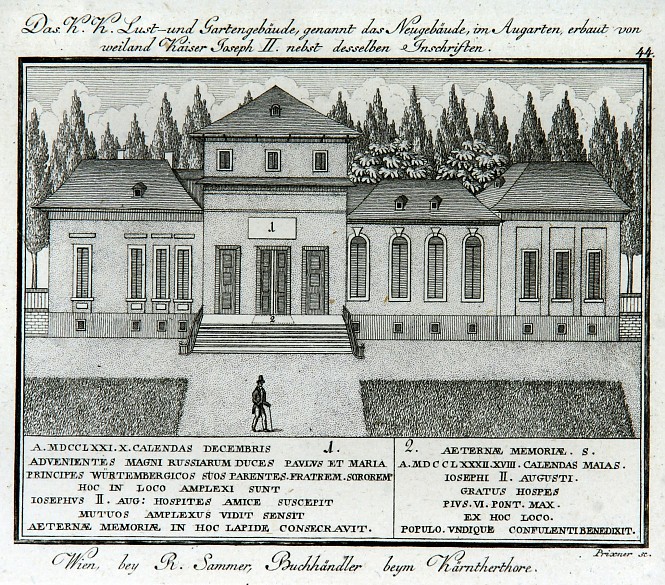

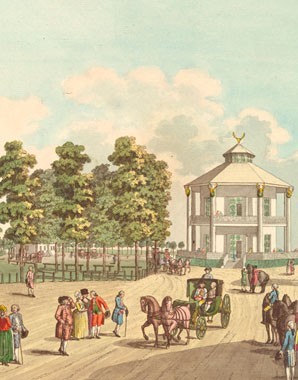

Joseph thus had little room for manoeuvre and had to concentrate his activities on a more symbolic level, for example ordering court ceremonial to be simplified, abolishing the formerly obligatory Spanish Mantelkleid for men and permitting them to appear in uniform at court, or opening the imperial parks (Schönbrunn, Augarten, Prater) to the public. One of the most important measures from this time was the transformation of the ‘Court Theatre beside the Hofburg’ into the ‘German National Theatre’ in 1776. The Burgtheater was now under the emperor’s direct authority, and he frequently intervened personally in its running. The former place of court entertainment had been turned into an educational institution for citizens.