An empire in two halves: the Compromise with Hungary

Following on from the foundation of the Austrian Empire, the Habsburg imperium was subjected to a further major reshaping in the second half of the nineteenth century – the Compromise with Hungary created the ‘Austro-Hungarian Monarchy’.

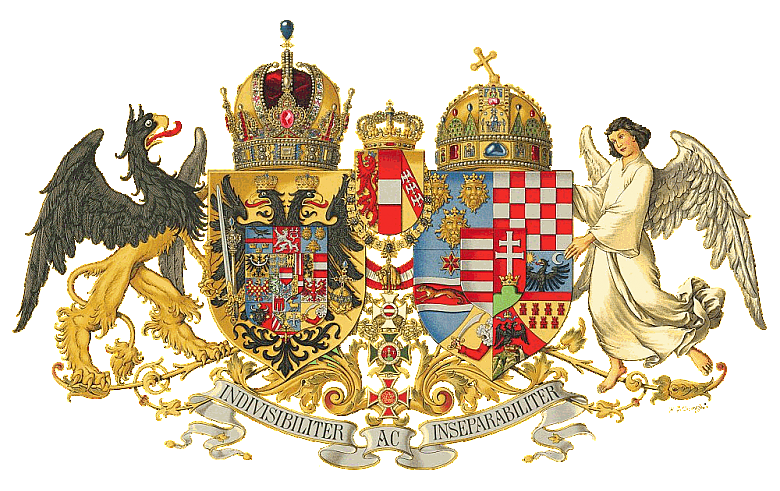

The ‘Middle Joint Coat of Arms’ (Mittleres gemeinsames Wappen) as prescribed in 1915 – that is to say, during the First World War – symbolizes the equal standing shared by the two halves of the Danube Monarchy: it represents the entire range of lands under Habsburg dominion are represented, the one shield having as its crest the imperial crown of Rudolf II and the other the royal crown of St Stephen.

The Compromise of 1867 ushered in important changes in the Danube Monarchy. It divided the Monarchy into two parts: the kingdom of Hungary, in which the Magyars made up only around one third of the population, and ‘the kingdoms and lands represented in the Imperial Council [Reichsrat]’, known more informally as ‘Cisleithania’ (the lands on ‘this’ side of the river Leitha) or simply ‘Austria’. While the Germans were the dominant force in the western part of the Monarchy, they likewise did not make up more than one third of the population. Austria and the kingdom of Hungary were linked through a union that was both personal (Franz Joseph being simultaneously emperor of Austria and king of Hungary) and real (foreign, military and financial affairs being conducted in common).

The financing of the common areas of policy was regulated by a quota laid down in the proportion 70 to 30 per cent in Hungary’s favour. In its home affairs – and thus also in its policy with regard to the nationalities – Hungary was independent and now had its own parliament and government. On 8 June 1867, Franz Joseph and Elisabeth were crowned king and queen of Hungary.

Like the German Austrians in the one half of the Monarchy, the Hungarians were now entitled to consolidate their own rights in the other half. However, not all the Monarchy’s ethnic groups were allowed to pursue their own national wishes, which were suppressed through strong measures taken not only from above by the state but also from below by the dominant social classes. One important example of this is the policy of Magyarization in Hungary, that is to say, the enforcement of conformity to all things ‘Hungarian’.