Vienna’s new art-loving bourgeoisie

In the nineteenth century the ruling house lost its leading position in the field of cultural patronage, being overtaken in music by the nobility and in particular the bourgeoisie.

Ignaz von Mosel made the observation on the apparently egalitarian effect of music in ViennaHere music daily performs the miracle that is only otherwise attributed to Love: it makes people of all social stations equal. Members of the nobility and of the bourgeoisie, princes and their retainers, those in authority and those beneath them sit together at one music stand, the harmony of the music making them oblivious to the disharmony of their social standing.

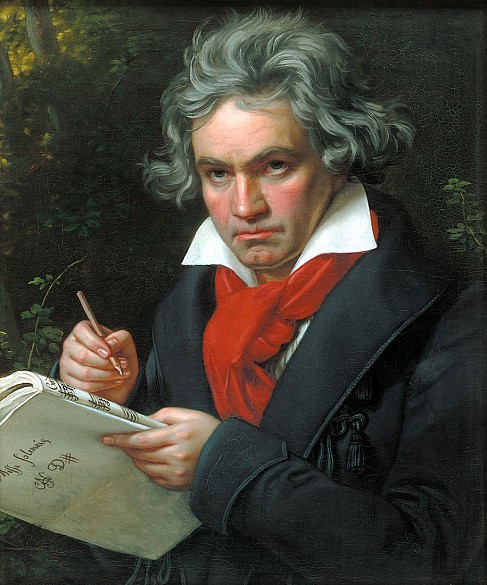

Amongst the composers active in Biedermeier Vienna were such famous figures as Franz Schubert and Ludwig van Beethoven, who settled permanently in the city in 1792. While Beethoven’s patrons were from the nobility, Schubert’s family and friends were solidly middle-class – the songs, the excursions to the country, and the musical soirées or ‘Schubertiads’ that are associated with his name all breathe the bourgeois spirit of the Biedermeier idyll.

Not a single really first-rank composer worked in the service of the imperial house in this period. Although Franz Schubert had been a court choirboy, he was unsuccessful in his application for the post of deputy master of the court music, nor did Ludwig van Beethoven ever become a court composer.

Music-making in the home enjoyed great popularity in the period between the Congress of Vienna and 1848, the year of the Revolution. Whether in bourgeois dwellings or noble or imperial palaces, ‘Hausmusik’ was a much-loved family pastime – Emperor Franz, for instance, played the cello in string quartets. The music business flourished: the shops turned over huge quantities of sheet music and instruments, new publishing houses emerged, such as that of Anton Diabelli, and new musical instrument factories were founded, most notably the piano-makers Bösendorfer, founded in 1828. Newly founded societies and orchestras also played their part in promoting music. Most notable amongst the former was the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde or ‘Philharmonic Society’. The birth of the first professional concert orchestra – the Vienna Philharmonic – took place in 1842, when members of the orchestra of the Court Opera took to mounting ‘Philharmonic Concerts’ on days when there were no opera performances.

There was great enthusiasm for music throughout Vienna. In 1828, the Vienna début of the ‘devil’s violinist’ Niccolò Paganini (1782–1840) in the Redoutensaal triggered ‘Paganini mania’. The audience response was so enthusiastic that Paganini prolonged his stay in Vienna and gave fourteen concerts. He was given the title ‘Imperial Chamber Virtuoso’ and became the object of a veritable cult that featured the wearing of Paganini hats and Paganini gloves.