Schloss Eckartsau: Emperor Karl on his way into exile

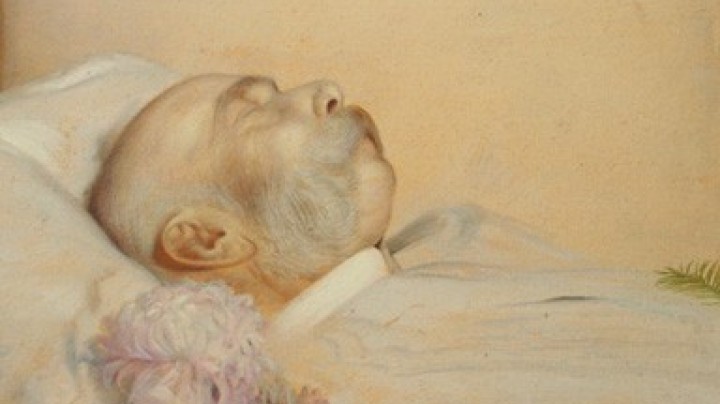

In the winter of 1918/1919 Eckartsau was the setting for the final act in the long rule of the Habsburgs: for three months the hunting lodge was the home of Karl, the last, disempowered Austrian emperor, before the imperial family set off into exile.

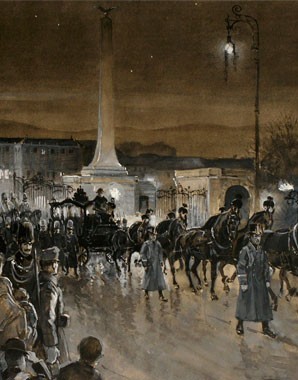

After Karl had signed the declaration by which he renounced his participation in the affairs of state on 11 November 1918, he left Schönbrunn Palace with his family. A convoy of seven automobiles set off and arrived at Eckartsau during the night.

The hunting lodge of Eckartsau lies to the east of Vienna in the wetland forests of the Danube and was one of a clutch of private Habsburg estates in the Marchfeld region of Lower Austria. In contrast to Schönbrunn, which was Crown property and passed more or less automatically into state ownership at the end of Habsburg rule, the private assets of the Habsburgs remained at first with the dynasty.

The lodge’s proximity to the Hungarian border offered a certain strategic advantage: although Karl had initially renounced any participation in government affairs in the Austrian half of the empire, he still hoped his sovereignty would be reinstated in Hungary. But two days later, on 13 November, a Hungarian delegation arrived in Eckartsau and obtained from Karl a declaration of renunciation. Karl refused to make a formal abdication as king of Hungary, just as he had as Austrian emperor.

As the weeks went by, Karl’s hopes of a rapid restoration of Habsburg power faded, and the family began to accommodate themselves to the difficulties of everyday life at Eckartsau. The general supply crisis and food shortage now also hit the Habsburgs with full force: after all, besides Karl and his family, there were around a hundred persons to provide for in their retinue and household. The hunting lodge was not equipped for long-term residence and the heating was inadequate. When influenza broke out among the lodge residents, there was no medication available.

In January 1919, State Chancellor Renner arrived unannounced at Eckartsau to urge Karl to leave the country at the earliest possibly opportunity, otherwise he would have to reckon with internment because of his refusal to abdicate. However, Renner was not received by the ex-emperor – apparently for ‘reasons of protocol’.

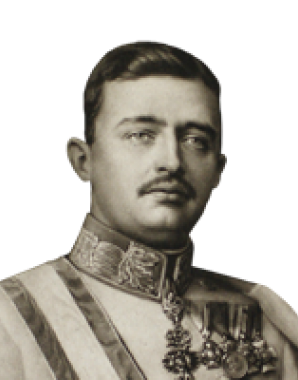

At the end of February 1919, an officer of the British Army arrived at the cold, snow-bound Marchfeld lodge: Colonel Edward Lisle Strutt communicated an address of solidarity from King George V to the ex-monarch in which Karl was assured of the ‘moral support’ of the British Government. Strutt had also brought with him urgently-needed supplies of food and medication. When Switzerland eventually expressed its willingness to grant exile to Karl and his family, Colonel Strutt organised their departure, which took place on 23 March. Before the family left, Mass was said in the lodge chapel, ‘Gott erhalte’ (the old imperial anthem) sung for the last time, then Karl drove to the railway station in nearby Kopfstetten, where the coaches of the imperial Court train were waiting. Karl had insisted upon going into exile ‘in due honour’: during the journey he wore the uniform of a field marshal of the former Imperial and Royal Army, which he only exchanged for civilian clothing shortly before crossing the border.

The train reached the Austrian-Swiss border near Feldkirch on 24 March. Before Karl crossed the border he issued the so-called ‘Feldkirch Manifesto’ in which he revoked his declaration of renunciation and submitted an official protest against his deposition. Then the last ruler from the House of Habsburg left the country.