The problem of the succession

The circumstance that Karl, a great-nephew of Franz Joseph, ended up becoming emperor is due to a chain of dramatic vicissitudes. When Karl was born in 1887 no one could have guessed that he would one day ascend the throne, as Crown Prince Rudolf, the only son of Franz Joseph, was the heir apparent.

Rudolf had married Stephanie of Belgium in 1881, a dynastic alliance that despite a positive start soon became unhappy due to their incompatibility. In 1883 a daughter, Elisabeth, called Erzsi in the family, was born. After Rudolf infected his wife with a venereal disease she was unable to have any further children.

After Rudolf’s tragic death at Mayerling in 1889 the succession passed to the nearest male relative of Franz Joseph. According to the provisions of Habsburg dynastic law, daughters were only permitted to inherit the title if there were no male members of the dynasty living.

In principle, the next in line to the throne was Archduke Karl Ludwig (b. 1833), the emperor’s younger brother. However, he was never officially designated heir to the throne – he was only three years younger than Franz Joseph and not a realistic choice: although Karl Ludwig frequently represented his brother on official occasions – earning him the nickname ‘Parade Archduke’ – he was otherwise considered unsuitable for this office. Extremely reactionary and anti-liberal in his views, even by Habsburg standards, Karl Ludwig died in 1896 from an infection he had caught from drinking water from the River Jordan while on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

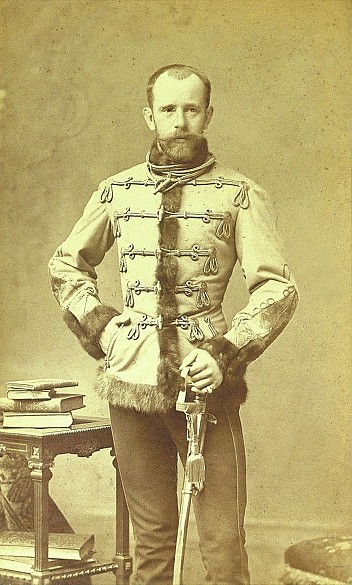

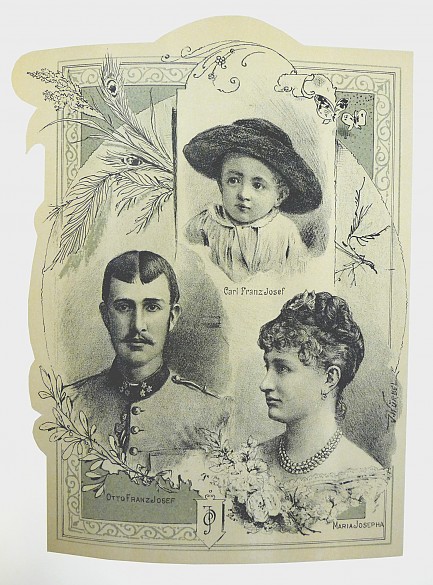

The succession thus passed to Karl Ludwig’s eldest son, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (b. 1863). At first it seemed as if this candidate would also bow out, as the archduke’s health was seriously affected by a lung complaint. At the Viennese court the numerous adversaries of Franz Ferdinand, whose difficult character made him unpopular, were already backing his younger brother, Archduke Otto (b. 1865), the next in line, as the more likely option. However, Otto, the ‘handsome archduke’, was regarded as the black sheep of the family on account of his scandalous lifestyle. He died of syphilis in 1906.

Franz Ferdinand, having recovered from his illness in the meantime, was officially declared heir presumptive in 1898. Relations between Emperor Franz Joseph and his nephew were however overshadowed by political controversy and personal dislike.

Franz Joseph had never forgiven Franz Ferdinand for insisting on marrying Countess Sophie Chotek, who was not a suitable match according to the strictures of Habsburg dynastic law. For the elderly emperor this was tantamount to a dereliction of duty on Franz Ferdinand’s part: to his mind, the obligation to contract a marriage with someone from one’s own rank in order to ensure the continuation of the dynasty had absolute precedence over individual happiness in love. However, Franz Ferdinand prevailed against all opposition and entered into this morganatic marriage. Although Sophie was raised to the rank of Duchess of Hohenberg, she was ostracized by the Court, which deeply wounded her husband. On the day of his wedding, the archduke was obliged to renounce membership of the imperial family and all associated privileges on behalf of his as yet unborn children. The descendants of this marriage live on today under the name of Hohenberg.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie at Sarajevo brought an unexpected turn of events. Franz Joseph’s reaction was typical both of his devoutly religious cast of mind and his concern to preserve the dynasty at all costs: he saw it not only as an attack on the honour of the House of Habsburg but also as the will of a higher power to reinstate an orderly succession.

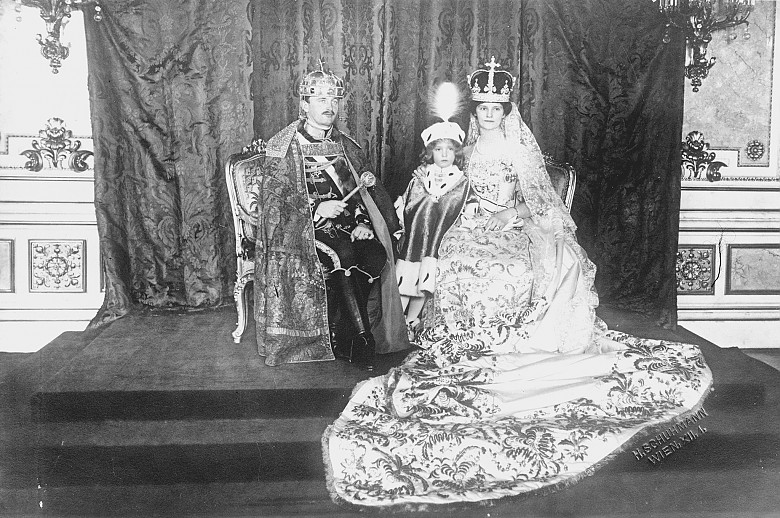

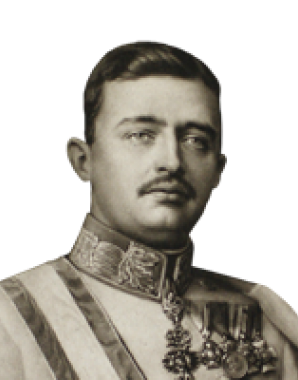

As Franz Ferdinand’s children were excluded from the succession, it passed to the eldest son of the late Archduke Otto, Karl (1887–1922). The great-nephew of Franz Joseph, he had married Zita of Bourbon-Parma (1892–1989) in 1911 – a flawless dynastic alliance intended to secure the future of the dynasty: 1912 saw the birth of the last crown prince, Otto (d. 2011), who was to lead the family into the era after the fall of the empire.