Quick money versus old aristocracy

In the nineteenth century the ‘first tier’ of society felt itself under threat from the up-and-coming bourgeoisie and the ‘second tier’ of society. Meanwhile these classes imitated the nobility.

The ‘old aristocracy’, the ‘first tier’ of society, took the leading position in both social and political matters, and they were closely interlinked with the imperial court. The court, however, became increasingly interested in the wealthy bankers and entrepreneurs who were able to provide the state and its ailing finances with a steady supply of money. The Emperor showed his thanks for this by ennobling them (raising them to the rank of aristocrats), making many members of the ‘second tier’ knights and barons. In this way more than 5,700 people were raised to the aristocracy in the Austrian half of the Empire in the years before the First World War.

Famous examples are the Rothschild and Epstein families, which had both amassed large fortunes through their banking businesses. The Court was happy to accept them as providers of money, but did not allow the members of the ‘second tier’ to reach the very top of the social ladder, not considering them to be fully ‘presentable at Court’. The old aristocracy had an ambivalent attitude towards the new financial nobility: on the one hand they feared them, seeing them as competitors in both society and politics and viewing them with suspicion. On the other hand they were prepared to co-operate with them in economic matters, for example in joint-stock companies. In their turn the members of the second tier tried to imitate the aristocracy and their lifestyle, and to this end they built magnificent town palaces along the Ringstrasse boulevard in Vienna.

The ‘old aristocracy’, of course, did not reside on the boulevard of the nouveaux riches and merely mocked the owners of the new palaces as ‘Ringstrasse Barons’. Caricatures appeared which showed the symbolic figure of a ‘Ringstrasse Baron’ relaxing on the balcony of his splendid palace, elegantly dressed and smoking a pipe.

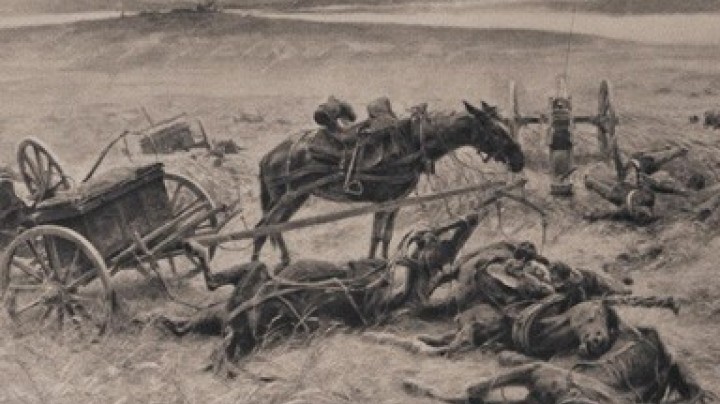

Both the old aristocracy and the second tier cultivated an extravagant and ostentatious lifestyle and this certainly played a part in giving Vienna, the seat of the Emperor, the status of a city of consumers. However, the old aristocracy came out of the stock exchange crash of 1873 more or less unscathed, because they had not become too deeply involved in speculative business and were the owners of real estate.