Lord of the manor has vacancies for peasants, with possible tenure for life – The origin of the peasant class

The decline in the population in the late Middle Ages gave the peasants an advantage in their negotiations with the manorial lords. One result of this was that farms could now be bequeathed.

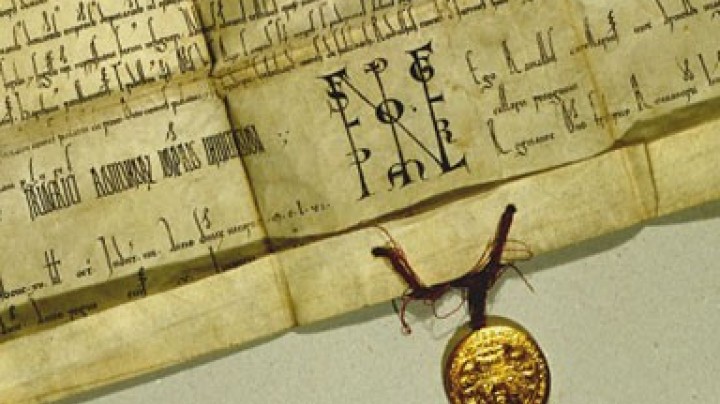

The drop in population caused by the plague had an effect on working conditions and wages in the towns. Since there was a shortage of labour, wages rose and servants were lured away by new masters. In the 1350s the council of the city of Vienna even issued regulations which forbade prospective employers to do this. In the countryside the lords of the manor also had to compete for the services of their subjects. During the period of population growth in the Middle Ages the so-called Freistift, a form of property holding granted by the lord of the manor that could be terminated by him at any time was the most oppressive form of fief. Since the manorial lords had more than enough people who were interested in being granted a fief to choose from, they often ended such a holding at the end of the year. However, when the situation changed in the wake of the plague they were prepared to make concessions, and these led to an improvement in the legal position of the peasantry. From the middle of the fourteenth century an increasing number of fiefs were granted for life or could even be bequeathed.

These changes meant that the peasantry gained greater security and greater freedom. What determined the social status of the individual peasant was now more and more the size of a farm he held and the area which could be cultivated. The peasant community, which regulated everyday matters as kind of autonomous body, became an important institution in relations with the manorial lords.

When it came to bequeathing property the peasants developed a number of strategies. When property was divided up, as was the prevalent custom in Vorarlberg, the west of Tyrol, the south of Styria and in Burgenland, the legacy was shared out among all male descendants. On the other hand there was the practice of passing on the entire legacy to one person, usually the eldest, or less usually the youngest, son. There were also numerous mixed forms of bequest. In the regions where in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries it was usual to have a single legatee some farms remained in the same form right down to the nineteenth century.