The last act – stately obsequies

‘It will be such a splendid festivity that I should most of all wish to walk behind my own coffin ...’ enthused Charles VI on the subject of his family’s funeral rites. The obsequies were indeed a magnificent ceremony, the allure of which only becomes fully clear in the context of the meaning behind it.

The demise of a Habsburg and certainly of a Habsburg ruler was an almost festive act. Just as did life at Court, so death also followed a strict set of rules. Today, the slavish adherence to particular ceremonies may appear to us devoid of meaning, yet for the rituals surrounding death and burial, just as with regard to the strictly-regulated daily routine and organization of other festivities at Court, it was important to heed the social and political significance of formalities. Through its actions upon the death and burial of a monarch, the ruling house demonstrated its piety, showcased the hierarchy which was so important to social life, and thereby enhanced the position of the ruling family.

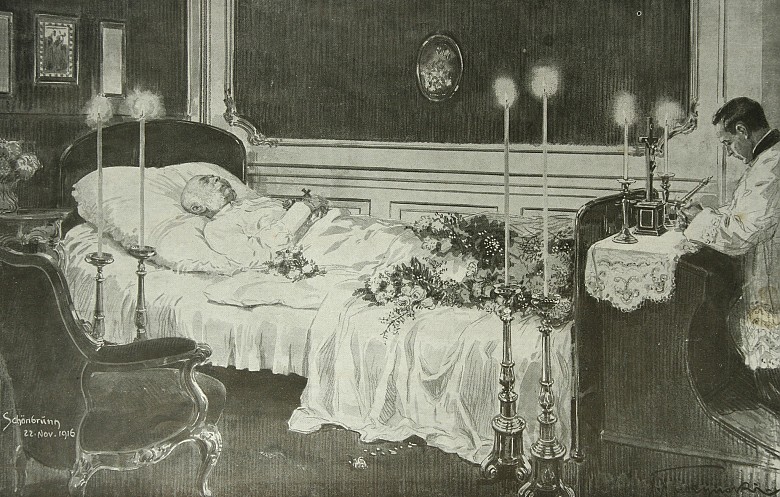

Now even for a monarch, death is a more difficult event to plan than a wedding or a coronation. Whenever possible, if a death was imminent, the family, including particularly the ruler’s successor, would gather at the monarch’s deathbed, accompanied by spiritual advisors and holders of high court office. Those assembled observed the monarch’s decease in keeping with Court ceremonial, bearing witness to the fact that indeed it was the ruler himself who had died, and that his death had occurred due to natural causes.

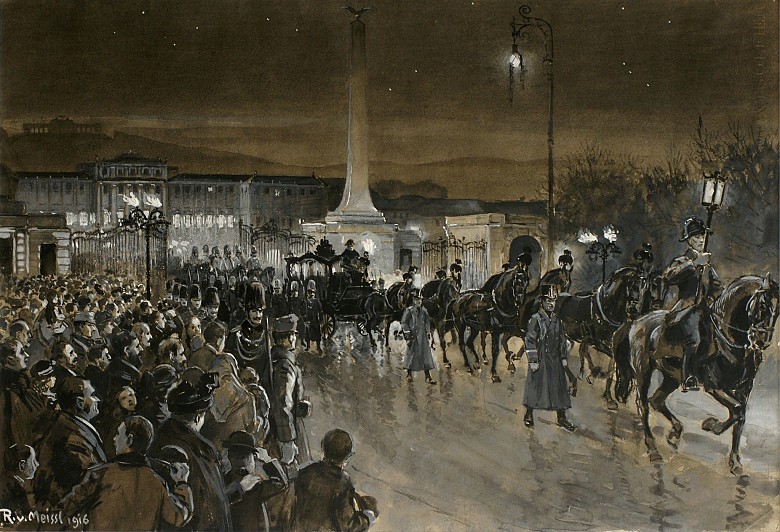

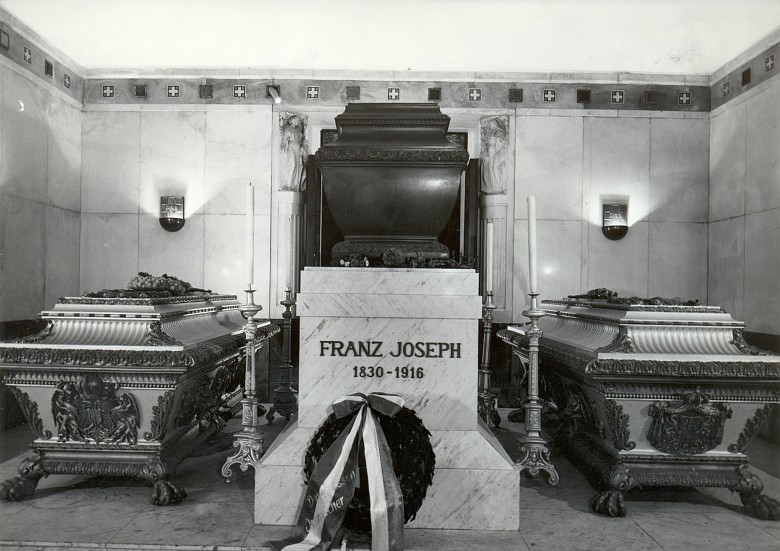

First of all, the body lay in state in the palace chapel at the Hofburg, and from there it was escorted in a solemn funeral procession to the church door of the Capuchin Monastery, where the custos escorted the cortège into the church which was draped in black. Following the mass, Capuchin monks carried the coffin by torchlight into the Imperial Crypt (Kaisergruft), where it was opened in order to verify in situ the identity of the deceased. Several weeks later, the wooden coffin was placed in the sarcophagus, which was then sealed.