Karl I: The peace emperor?

How quickly ‘harmless’ war games can become terrifyingly serious was shown in the case of Emperor Karl. But the last ruler of the Danube Monarchy was unable to make much difference to the course of the First World War.

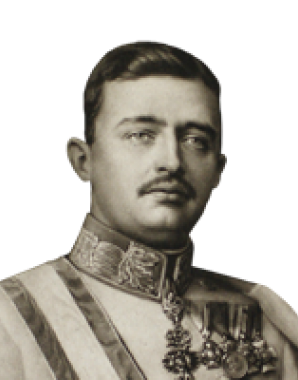

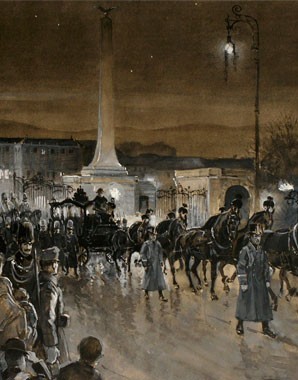

The old Emperor Franz Joseph, his successor Karl and the young Archduke Otto having fun playing with tin soldiers – in the First World War, however, the lithograph’s image of a harmless family idyll was for innumerable men and women to become the experience of war in all its grim reality. When Franz Joseph died in the middle of the First World War in November 1916, he was succeeded as Emperor of Austria by his great-nephew Karl, who was to be Austria’s last Habsburg ruler. Politically entirely inexperienced, Karl did not play a leading role in the world war – in the question of the nationalities, for instance, he had little scope for action. His attempts at diplomatic mediation proved unsuccessful, particular famous among them being the so-called Sixtus Affair in which Sixtus and Xavier, two of his wife Zita’s brothers, acted as go-betweens in secret peace negotiations with France. In a letter to Sixtus, Karl committed himself to supporting French territorial claims in Alsace-Lorraine, but his secret endeavours failed. This ‘affair’ became embarrassing when early in 1918 the letter to Sixtus was published by France and Karl adamantly denied that he had engaged in the negotiations at all. Consequently, Austria finally subordinated itself to the war policy of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

In a speech on behalf of the Imperial-Royal Austrian Military Widows and Orphans Fund in 1916, Karl still referred to the Monarchy as heading towards ‘a great goal’ in the world war. This speech not only underplays the horrors that soldiers and civilians had to go through in the war but positively glorifies them, presenting them as service for a greater cause. While historians gladly concede that Karl acted in good will in his peace negotiations, as a ruler he was way out of his depth. The fact that he is now accorded the appellation of ‘peace emperor’ only conceals the fact that innumerable men and women had to die in his name.

In October 1918, Emperor Karl made a belated and unsuccessful attempt to save the Monarchy through a ‘manifesto to the peoples’ intended to lead to the creation of a kind of federal state with autonomous national units. On 11 November 1918 he relinquished his involvement in government but did not formally abdicate. After he had been sent into exile in 1919, the year 1921 saw him making two bids for a restoration in Hungary, from which it is clear that the Habsburg dynasty’s age-old territorial claims had not been given up with the downfall of the Monarchy. The fact that Emperor Karl chose the motto of the Pragmatic Sanction as his own – ‘Indivisibiliter ac inseparabiliter’ (‘Indivisibly and inseparably’) – was to appear particularly grotesque in the light of the disintegration of his empire.