Like father, like son …

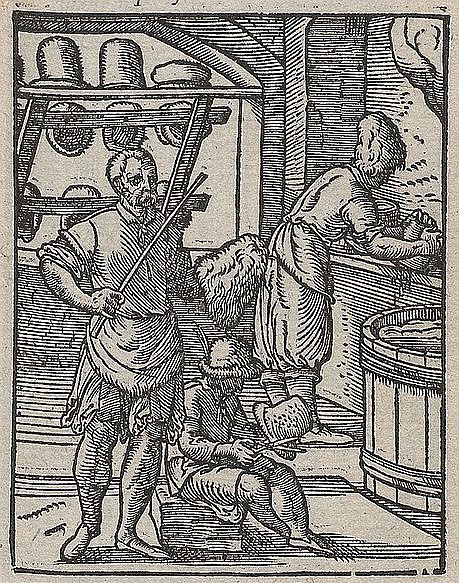

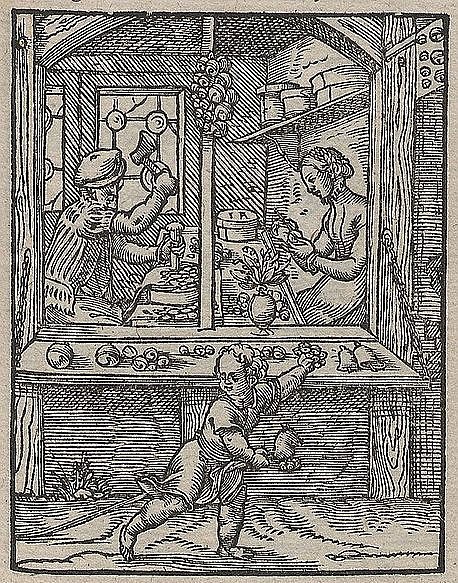

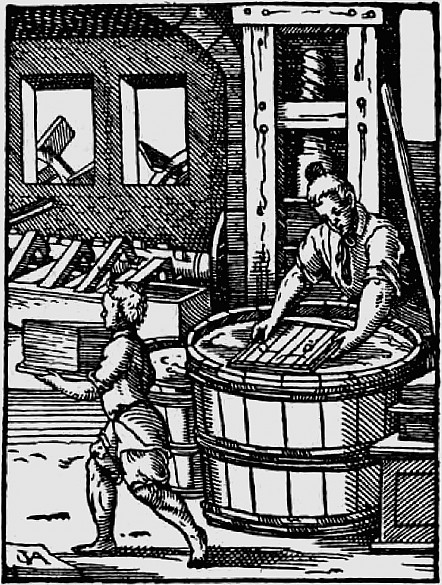

Children acquired both domestic and manual skills directly from their parents.

Children were normally brought up within the household-family, where they were gradually introduced to the adult working world they would soon become a part of themselves. Whereas in the country schooling played only a minor role, the children of artisans and craftsmen in the towns would receive some kind of elementary education. The offspring of aristocratic families were also prepared for their future duties early on in their lives, and they were forbidden to fraternize with children of lower social standing. Moreover, in comparison to children from other social strata, aristocratic children were under the more direct control of their father, without whose permission nothing happened.

Regardless of their age, children remained part of the household-family, and thus under their father’s authority, until they married. Children included both the father’s own offspring as well as any other children living in the same household, as they all played a part in its running. Children of both sexes from poor families in particular were often sent to work on other farms in the vicinity as farmhands. In craft businesses, the young men took to the road as journeymen, while the girls went into service in other households. When they married, children would receive a dowry or part of their inheritance. The sons of peasants took over their parents’ farms, craftsmen their father’s workshop, and the offspring of the nobility were prepared for the daily routines of aristocratic life. In general, girls were taught how to run a household.

Children were generally treated like adults in the early modern times, and it was not until pedagogical principles were widely recognized and a school system established that childhood and youth came to be seen as a separate phase of life. Although journeymen’s associations existed in the towns and there were young men’s societies in villages where they spent their free time, they were always expected to emulate the behaviour of adults wherever they went. The folk imagination and the art of the time conceived of man’s progression through life as a kind of staircase, with young adulthood constituting a stage in its own right. It was not until the French Revolution and the Sturm und Drang movement that youth came to be regarded as a phase of rebellion and protest.