Exhibit the world – Vienna as World Exhibition venue

To present the power and splendour of the Habsburg monarchy: that was the aim of the Vienna World Exhibition of 1873. It also provided the Emperor of Germany, the Tsar of Russia and the King of Sweden with a stage for international politics.

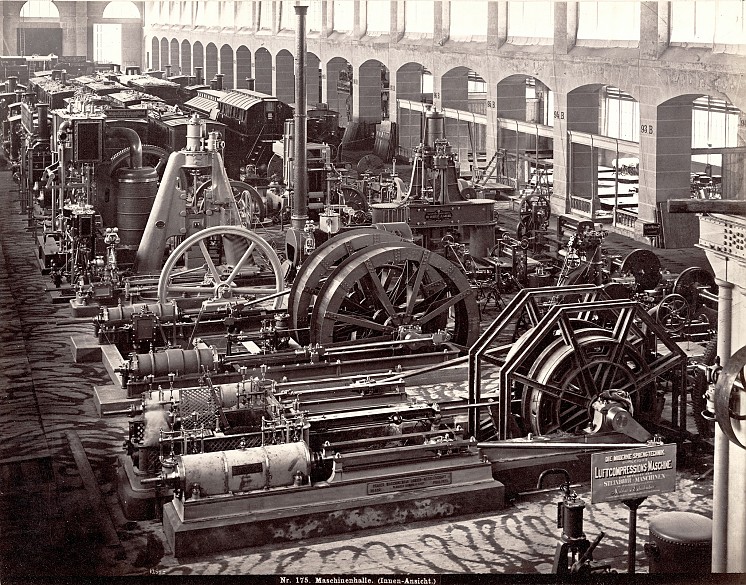

On top of the Rotunda, the building which was the symbol of the Vienna World Exhibition of 1873, there shone a replica of the Imperial Crown made of gold-plated wrought iron. The imperial dynasty was not only represented symbolically at the Exhibition but also headed the organizing committee: Archduke Rainer chaired the Imperial-Royal Commission for the World Exhibition and Archduke Karl Ludwig was the honorary patron. They were probably chosen because they had openly shown their interest in science and technology. The Rotunda was the conspicuous central building, a gigantic structure which served as the focus of the World Exhibition, with four rectangular galleries, each 190 metres long, leading away from it. There was a Palace of Industry and a Hall of Engines (between 700 and 900 metres long), in which more than 1,000 exhibitors presented their products. The most important building material was iron, whose use was definitely regarded as modern in the nineteenth century – think, for example of the Eiffel Tower, built for the Paris World Exhibition of 1889. In order to make room for the exhibition’s numerous buildings, parts of the Prater park were opened up and built over – up to then the area had been more or less untouched countryside.

What was new was that there was a pavilion devoted exclusively to women, in which the organizers, however, equated women’s work with arts and crafts. Since it was above all middle-class women who made products in this field, all other products made by women were ignored. This meant that women continued to be associated only with arts and crafts: what they produced was described as beautiful, charming or artistic, but not as useful or innovative.

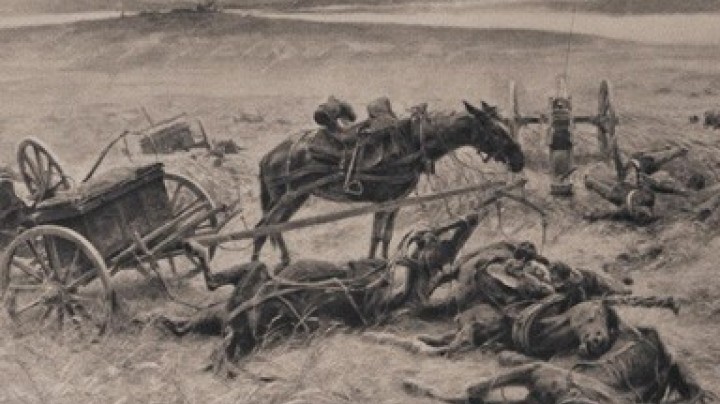

The exhibition was intended not only to fill visitors with enthusiasm but also to inform them about new developments in technology and hence to promote industry and increase sales. Not least because visitors were kept away by a cholera epidemic and the stock exchange crash, profits were far below expectations and the state had to finance the entire cost of the Exhibition.