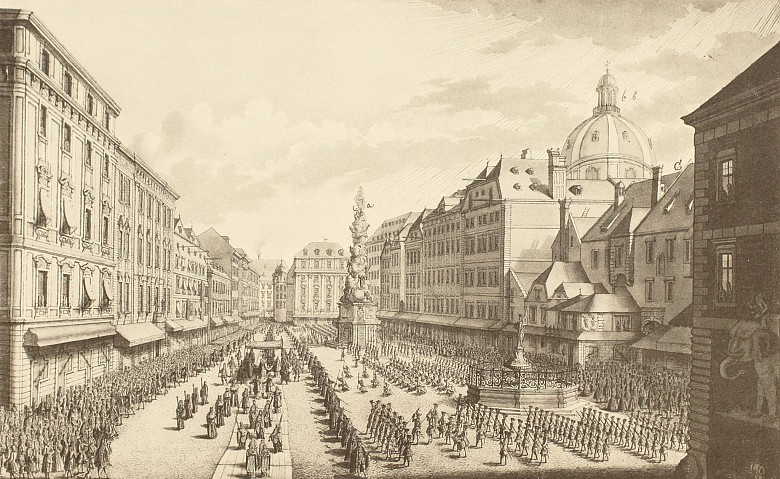

The Corpus Christi procession – ‘God’s Court Ball’

Veneration of the Eucharist was a leitmotif of Habsburg piety. The Corpus Christi procession was always celebrated with great opulence; it was not only a resplendent spectacle for the general public, but the event for demonstrating the way the Habsburgs saw themselves as Catholics.

Zitat aus: Fugger, Nora von: Im Glanz der Kaiserzeit, 2. Auflage , Wien 1980, S. 77; zitiert nach: Winkelhofer, Martina: „Viribus unitis“ Der Kaiser und sein Hof. Ein neues Franz-Joseph-Bild, Wien 2008, S. 123-124Anyone who has witnessed this imposing, colourful scene will find it hard to forget: the gold-encrusted uniforms of the highest dignitaries, the glorious raiment of the ladies, their gold-embroidered court trains carried by pages and lackeys, the splendour of the liturgical vestments, the smart comportment of the guards in their picturesque uniforms, the multitude of court servants, from the stable grooms upwards, all in gold-trimmed, medieval-style liveries and costumes. And despite this kaleidoscopic variety of the individual participants, the overall impression was one of harmony.

The veneration of the Eucharist, the veneration of the Body of Christ in the form of the consecrated host, had been regarded since Rudolf I as one of the central expressions of the Habsburgs’ strength of faith. An oft-quoted legend has it that the Habsburg ruler met a priest who was carrying the host to a sick person for the sacrament of Extreme Unction. As a sign of his humility before the sacrament, Rudolf is said to have given the priest his horse and accompanied him on foot.

This was a very popular motif and found a fair number of imitators in the dynasty. It is recorded that several Habsburgs humbly genuflected before the host in the monstrance, or accompanied the priest on foot and with bared head.

The veneration of the Eucharist was one of the most elemental expressions of Catholicism and fostered deliberately at the Viennese Court during the age of schism as a sign of loyalty to the Roman Church. Thus in times of exceptional danger, the emperor decreed that the Holy Sacrament be displayed for veneration in precious and elaborate monstrances on church altars to petition divine assistance.

The Corpus Christi processions were held at the Viennese Court from the late sixteenth century as a clarion signal to sectarian adversaries and as great public events to demonstrate supremacy of faith over the city. Accompanied by the sounds of drums and trumpets, the procession led from the Hofburg chapel through the main squares and streets of Vienna’s inner city.

The procession was headed by three priests, followed by a delegation of Court officials. After them came the Court clergy in full canonicals, then the Court and state dignitaries in full court dress, among them, ordered according to rank, the privy councillors and ministers, followed by the archdukes.

The baldachin was carried by four noble chamberlains and held aloft over the Hofburg parish priest, who held up the monstrance containing the host. Immediately behind it walked the emperor with bared head and accompanied by the Obersthofmeister (head of the Court household) and flanked by his captains of the guard. The tail of the procession was taken up by the ladies of the Court, led by the empress and other female members of the family, followed by the ladies-in-waiting, the wives of the highest Court dignitaries.

The Corpus Christi procession remained the most striking sign of the institutionalized piety of the Court until the end of the monarchy, since this public demonstration was a clear statement that Catholicism remained the state religion for the House of Habsburg, even if the empire was multi-confessional.