‘Sponsored by Fugger’ – Trading houses as financial backers

It was not unusual for the Habsburgs to make use of the services of private financial backers. Despite the high risks this was good business for both sides.

The regular revenue which the Habsburg rulers had at their disposal was not really sufficient, especially in times of war. In particular when they needed money quickly they turned to private lenders. These were able to use bills of exchange to provide large sums of money relatively promptly, even when these had to be transferred over long distances. Moreover, the lenders were often to be found among those merchants who, for example, supplied culinary delicacies or other luxury goods to the imperial Court. Such lenders made a considerable amount of money from these deals with the ruling dynasty and the aristocracy, because the interest charged was around eight per cent per year – or even more. Admittedly, such loan deals entailed the risk that rulers and aristocrats might not repay their debts. On the other hand the increasing indebtedness of the rulers made them increasingly dependent, a circumstance which restricted their room to manoeuvre in military and political affairs. The estates represented in the provincial diets also played an important role, since they could in some cases pay off the debts or act as guarantors for new loans.

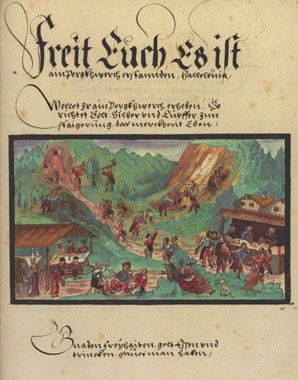

The banking and trading house of Fugger from Augsburg was particularly well-known. Its links with the Habsburgs go back to the late fifteenth century, when the Fuggers lent Archduke Sigismund of Tyrol 500,000 gulden. In return they were granted rights to the yield from the silver mines in Schwaz on favourable terms. Trade in metal remained an important part of their business until well into the sixteenth century. Money from the Fuggers was also used to pay bribes to the electoral princes in connection with the election of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, and he later used loans provided by the Fuggers to finance the war against the Schmalkalden League of Protestant princes in Germany in 1546-7. It was above all Anton Fugger who had close ties with the Habsburgs and lent them some 400,000 ducats from his personal fortune at the time of the Princes’ Revolt in 1552. In this way the Fuggers could on the one hand make large profits from their dealings with the Habsburgs, but on the other hand by the middle of the seventeenth century they had lost some eight million Rhenish gulden because the Court Chamber (Hofkammer) did not settle its debts.