Punctual town dwellers, timeless peasants, leisurely women – Or: why clock time is not for everyone

The closing times of inns, the working hours of journeymen, the opening hours of markets: from the late Middle Ages all these were determined by clock time. It was in particular the men living in towns who saw themselves as the ‘lords of time’.

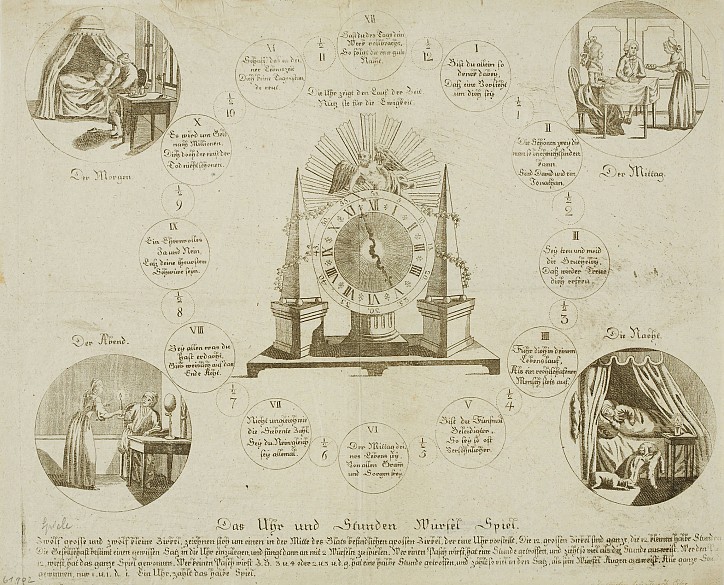

In the late Middle Ages and the early modern period many town dwellers were of the opinion that exact clock times did not have any meaning for country folk. In fact people living in the countryside really did calculate time in their own way: what mattered was not so much an exact date and an exact time of day as indications of how much time was needed for a certain activity, for example to eat a meal or to get from A to B. However, country people could not simply ignore ‘clock time’: for example, they too had to keep to the fixed times at which they were allowed to sell their produce at markets in towns. Moreover, from the seventeenth century on clocks were placed on church towers in many villages, so that the times of church services could be laid down exactly.

Town and country were symbolically separated by the opening and closing of town gates at fixed times. The order created by abstract clock time played an important role in town life and was seen as an expression of moraliity, civilization and modernity. The upper ranks of the bourgeoisie even saw clock time as something that belonged to them rather than to the aristocracy, whom they accused of owning clocks and watches only as status symbols and fashionable accessories and not for the sake of their function as timepieces.

Since the Middle Ages men and women had been thought to have different relationships with time. In allegorical representations women stood for tranquillity and leisureliness, while men stood for speed and power. There were even times when it was only men who were allowed to own a clock. From around 1700 the tradition grew up among the bourgeoisie of giving young men a clock or watch at their confirmation. Their entry into the society of adult men was symbolized by handing them the means to control time for their wives and children. It was not until the twentieth century that girls were also given a watch when they were confirmed.