New in the catalogue: apartments with running water – Too little and too much water in Vienna

Although the Viennese lived beside the beautiful blue Danube, they preferred water from the mountains. Water from the Danube was not really good for drinking.

Although Vienna lies on the Danube and is surrounded by plenty of water, for many centuries it was difficult to supply the city’s population with water for drinking – or for other purposes, for example for fire-fighting or for horses. There were shortages, especially during periods of drought. When, in 1835, shortages led to water being rationed, the Viennese attempted a rebellion, with the result that Emperor Ferdinand I gave orders for the construction of a water pipeline which would filter water from the Danube. Although this did reduce the problem it did not provide a permanent solution since by no means all houses in Vienna could be supplied with water. The problem of the water supply grew as the nineteenth century progressed: firstly because the sharply increasing population needed more and more water, and secondly because the groundwater became more and more polluted as a result of the inadequacy of the city’s sewerage system and the consequent danger of outbreaks of epidemics of cholera or typhus. To improve matters it was planned to build a pipeline for Alpine water, which would bring water to Vienna from springs some eighty kilometres distant. This was financed by the City of Vienna and officially opened by Emperor Franz Joseph in 1873, the year of the World Exhibition. The pipeline was intended to supply not only the city’s palaces and the buildings along the Ringstrasse boulevard but also the houses in the suburbs where the working classes lived.

As this project was extremely expensive there were charges for water; these were based on the consumption of 34 litres (later reduced to 25 litres) per day and per person for each household. By way of comparison: today the average daily consumption of water in Austria is 150 litres per person, while in India people must make do with 25 litres. In Vienna the inner-city districts consumed far more water than the outer suburbs, the result of the different levels of sanitation in the houses. It was in the inner districts that these were more likely to be provided with bathrooms and toilets inside each apartment. It was not until a second Alpine water pipeline was completed in 1910 that the continuing problems with the water supply could be solved on a long-term basis.

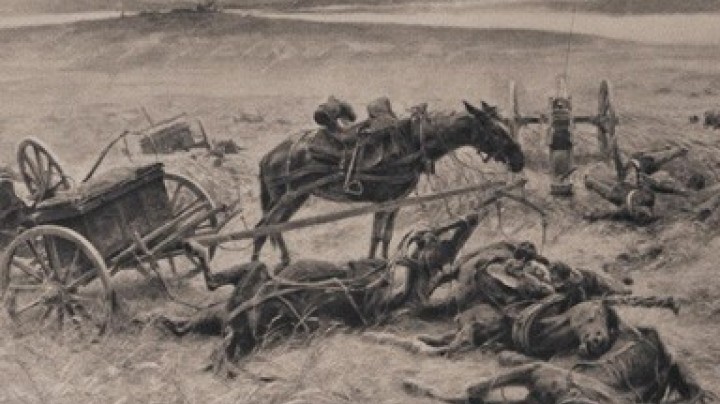

However, the Viennese had problems not only with water shortages but also with there being too much water. Both the Danube and the Vienna River flowing into it repeatedly caused flooding as a result of high water levels and pack ice. It was not easy to solve the problem, because even after the Danube was regulated (1870 to 1875) flooding still occurred. For many years there was no political will to regulate the Vienna River; this was not done until the turn of the century (1895 to 1906).