Named for Imperial Highnesses – Railways create new mobility

The Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway, the Empress Elisabeth Western Railway, the Emperor Franz Joseph Railway and the Crown Prince Rudolf Railway – even when you made a journey (by train), the Habsburgs were omnipresent.

Building and setting up railways in the Habsburg Monarchy was by no means a process free of conflicts: doctors attested that the railway endangered health, postal service employees feared for their jobs, and the police expected problems in keeping track of people. Franz I rejected the first application to build a railway line submitted by the banker, Salomon Rothschild, because he saw in it a danger to absolutism and to the Monarchy. His successor, Ferdinand I, approved the construction plan, with the result that the railway line in question was named the Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway. The first major section, linking Vienna and Brno, was completed in 1839.

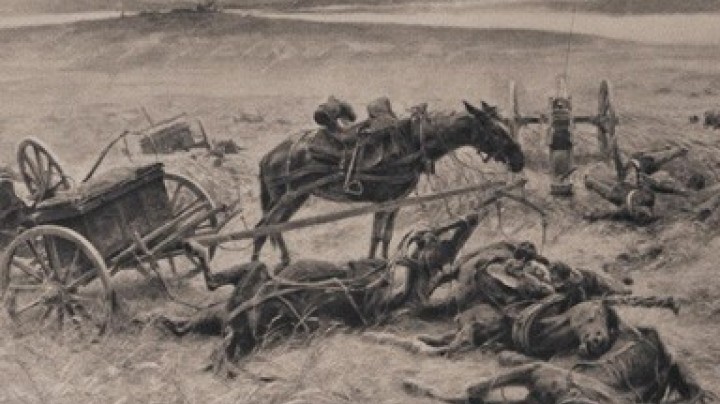

Those who were sceptical about railways felt they had been proved right when the first train on the line crashed on its way back from Brno to Vienna. The police’s fear that there would be more work for them to do also proved to be justified, at least initially: at first passengers had to collect a permit for their journey from the police on the day before they travelled, to have this stamped at their destination and then to return it to the police when they arrived back in Vienna. In spite of the effort needed it was worthwhile taking the train: take the journey from Vienna to Graz, which took nine hours compared with the twenty-nine needed by post coach. It was not only people’s scope for mobility which the railways changed: they also changed the towns themselves, including the townscape of Vienna. The terminus stations which were built in Vienna – terminuses because it was here that the railway lines began and ended – were enormous buildings designed to impress, with ‘no cost being spared’, as the architect of the North Station put it. However, they had to take into account the political and military concerns of the Monarchy. The East Station, for example, had to be a low construction, so that, in the event of an uprising or a revolution, the guns in the nearby Arsenal would have a clear view of targets in the city centre.