How unemployment became a social problem

If sources can be trusted, in 1790 some 66% of those who died were paupers. In particular the non-working and out-of-work sections of the population became the focus of the debate on poverty

In order to exploit fully the working potential of subjects by means of a mercantilist population policy, the subjects of the Monarchy were statistically recorded and ‘poverty’ was addressed as a social problem. As in economically successful states such as England and the Netherlands, a new work ethos, based on hard work and orderliness, was to be introduced in the Catholic Habsburg Monarchy. A consequence of this was discrimination against the non-working population and degradation of the figure of the beggar.

Since many areas of employment were still unregulated, state economists such as Heinrich Gottlieb von Justi believed the origins of the ‘sluggish, sleepy and inactive subjects’ were to be found in prodigal Catholicism; he felt that the very virtue of alms-giving simply encouraged ‘beggary’.

In place of charity, discipline now became the norm in dealing with the affected strata of society. Work was regarded as a fitting means of education to keep people from idleness. Workhouses and educational establishments were set up to produce hardworking subjects with fixed abodes.

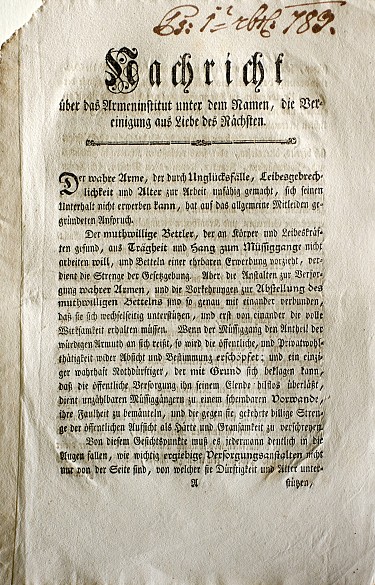

For this purpose two groups were distinguished: persons ‘incapable of work’, including invalids, the old and the sick, were supported – since their poverty was not of their own making – by church and civic institutions of the responsible authority. The ‘workshy’, by contrast, were treated as criminals. Gypsies, bands of thieves, beggars, vagabonds, hawkers, entertainers and so on – together with certain professional groups and others of no fixed abode, came under the general heading of the ‘dreadful state of beggary’. Decrees, pronouncements and prohibitions resulted in regular ‘beggar-hunts’ and, in part, to their deportation to remote regions of the Monarchy. Punishments of public humiliation and hard labour, or lifelong stigmatization, turned those concerned, including many women, into social outcasts. The selection of these people and the severity of the social and disciplinary measures imposed were often dependent on random decisions by the authorities, and sometimes widows, journeymen and invalids ended up being deported.