Frederick V: death and legacy

Frederick V was one of the longest-ruling Habsburgs in history, reigning for fifty-eight years in Inner Austria and for fifty-three years as head of the Holy Roman Empire.

In neither case did his rule go unchallenged. Nonetheless, in the long term he was able to assert himself, often solely due to his physical robustness that led to him surviving most of his opponents.

Frederick’s life was marked by a unique dichotomy between aspiration and reality. Severely limited in terms of realpolitik by internal family conflicts and powerful adversaries such as Matthias Corvinus, he nonetheless laid the foundations for the rise of the Habsburgs as a major European power.

It is to Frederick that the dynasty owed its regained hold on the claim to leadership in the Empire after it had been in danger of declining to a merely regional power in the face of Luxembourg dominance. Starting with Frederick, his descendants (with a brief interruption from 1740 to 1745) were to bear the imperial crown until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. Frederick occupies a special position here, as he was the first in the dynasty to bear the title of emperor and remained the only Habsburg to follow medieval tradition in undertaking the hazardous journey to Rome in order to be crowned by the pope.

Frederick’s actions were shaped by his extremely pragmatic, prosaic character. Neither radiant monarch nor brave warrior – he is sometimes referred to ironically as the ‘Empire’s arch-night cap’ (meaning a ‘slow-coach’) – he was nonetheless steeped in the concept of emperorship and convinced of his dynasty’s chosen role. He developed an exaggerated sense of monarchical identity despite – or perhaps because – his numerous adversaries had so often shown him the limits of his power.

Although he was conservative by nature and his thinking was shaped by medieval concepts, he entertained contacts with humanists. His secretary was the important historian and poet Enea Silvio Piccolomini (later Pope Pius II), who during the years he spent in Vienna and Graz (1443–1455) exposed the Habsburg court to humanist currents and the influence of the Italian Renaissance.

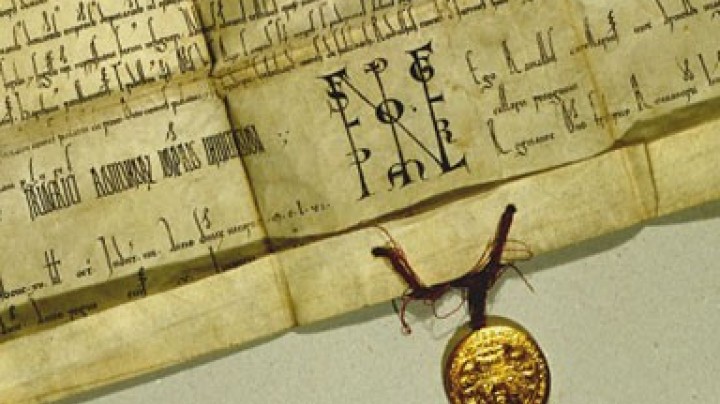

In his physical appearance Frederick conformed to the classic Habsburg type. He had a longish face, a prominent nose and was tall and thin, He was interested in astronomy, astrology and the occult sciences. The emperor collected precious stones on a large scale, not only for their value but also because he was convinced that they possessed magical properties. The meaning of his personal cipher AEIOU is still disputed by scholars.

Frederick died in Linz in 1493. He had been suffering from senile gangrene, a tissue necrosis that leads to parts of the body dying off due to an insufficient supply of blood and therefore oxygen. One of Frederick’s legs had become affected, and to prevent it poisoning the rest of his body it had to be amputated. By now aged seventy-eight, the emperor survived the operation, which took place with the patient fully conscious, only to die two months later, probably of a stomach infection. According to contemporary sources, Frederick, who had always had a predilection for fresh fruit, died from a surfeit of melons.

The emperor was buried in Vienna’s St Stephen’s Cathedral, which thanks to Frederick – here too following the model of his venerated ancestor Rudolf IV – underwent its final phase of construction. Frederick’s monumental tomb is a major work of the late Gothic era but was not completed until 1513. His heart and entrails were interred in the parish church at Linz.