Franz Stephan: patron of the sciences and financial wizard

Maria Theresa’s husband was very progressive in outlook and brought many new cultural and intellectual ideas from his native country in western Europe.

Thanks to Franz Stephan the French element at the Viennese court was reinforced. The private correspondence of Maria Theresa’s family was written mainly in French with a sprinkling of German words, often in Viennese dialect.

Franz Stephan constituted a link with the intellectual world of western Europe, where the Enlightenment was in full swing. Informed by rational principles, the emperor was open to these new currents. Significantly he was also a member and patron of the secret society of the Freemasons. Very popular among the liberal elites of Europe, this association wanted to reform society on humanist principles, freeing humankind from the fetters of religious intolerance and feudal oppression.

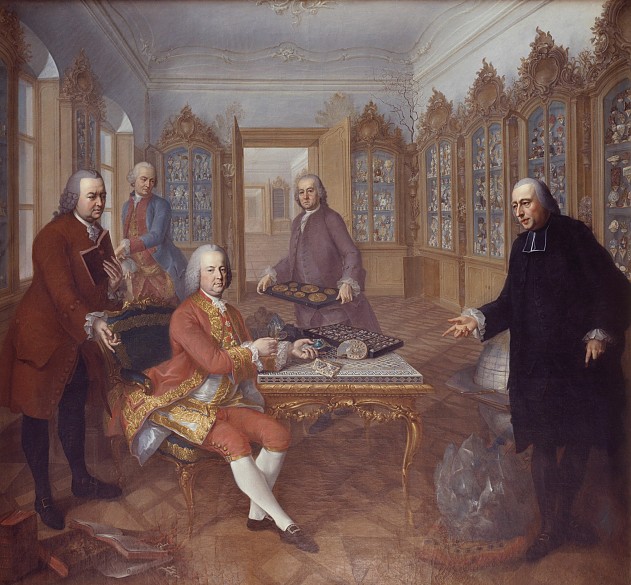

Being only very loosely involved in the affairs of government, Franz Stephan created his own realm in the ‘Kaiserhaus’, a palace on Wallnerstrasse in Vienna. There he was able to pursue his scientific interests unhindered, with a laboratory, a library and space for his collections. Known at that time as the ‘Naturalienkabinett’, this institution was later to form the core of the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Here the emperor surrounded himself with a self-contained company of scientists, engineers and artists from across Europe. He was instrumental in persuading Gérard van Swieten to move to Vienna as imperial physician in 1745. Van Swieten was subsequently responsible for reforming the University in Vienna and the Court Library as well as laying the foundations for improvements in the Viennese School of Medicine, which was to achieve an international reputation for excellence during the nineteenth century.

The most tangible results of Franz Stephan’s endeavours have been preserved at Schönbrunn. In contrast to the rest of the park, which foregrounded aesthetic principles and was intended to reflect the majesty and pomp of the dynasty, a part of the gardens was designed as an image of the concept of reason and order imposed upon what was considered to be the chaos of Nature. In 1752 Franz Stephan established the menagerie at Schönbrunn, the oldest still extant zoological garden in Europe. This was followed a year later by the Botanic Garden, known as the Dutch Garden in acknowledgement of its first director, Adrian van Steckhoven, who had come from Holland. The emperor authorized an expedition to the Caribbean led by Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin to acquire exotic flora and fauna which took place from 1754 to 1759. Franz Joseph was personally involved in and well informed about all these projects.

Another interesting aspect of Franz Stephan’s personality is the financial talent that enabled him to accumulate a large private fortune within a very short space of time. He acquired estates in Lower Austria, Hungary and Moravia, and had been enfeoffed with the Duchy of Teschen in the Austrian part of Silesia by his father-in-law Charles VI. On his demesnes at Holitsch and Sassin in Upper Hungary he created an example of an early industrial empire with highly profitable textile and pottery manufactories.

This wealth enabled him to extend loans to Maria Theresa and the permanently exhausted state coffers. He also benefited from major contracts awarded by the Austrian military administration. Rumours that he had made money unlawfully by overcharging on these contracts, or even that he had supplied arms to Prussia, cannot be verified.

After Franz Stephan’s death this huge complex of assets formed the foundation for the Habsburg ‘family support fund’, a trust which provided for the non-ruling members of the family. The majority of his monetary assets was used by his son and successor Joseph II to settle the government debt that had accumulated during the course of the Seven Years’ War.