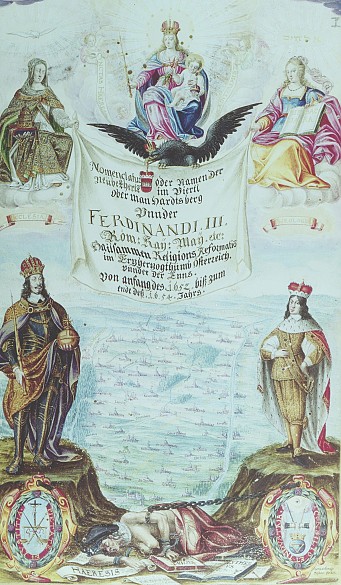

Ferdinand III: the forgotten emperor

Ferdinand III is one of the less well-known members of the Habsburg dynasty, despite the fact that important changes in political course took place under his rule. The outcome of the Thirty Years’ War had led to an acceptance within the dynasty of the limits of imperial power in political and religious affairs. However, these painful concessions in the Holy Roman Empire contrasted with the strengthening of dynastic power within the Habsburg Monarchy.

The most important consequence of the new peace framework for the Empire was that a way was found to defuse the religious tensions which had weakened the cohesion of the Empire since the schism of the Lutheran Reformation. The coexistence of the various Christian denominations in the Empire was placed on a sound basis.

Moreover, the imperial Estates were granted full sovereignty and the right to independent foreign and alliance policy. The Holy Roman Empire was now a federation comprising around 300 medium-sized, small and very minor states, of which only the major regional powers of Bavaria, Brandenburg, Saxony and Hanover could in reality make use of the opportunities arising from the latter provision. Imperial power had nonetheless been massively curtailed: the end of the hegemony of the Habsburg emperors in the Empire had arrived. As a result the Habsburgs concentrated their efforts on their patrimonial dominions, which now started to develop independently of the Empire at a more rapid pace than before.

The new constitutional basis of the Peace of Westphalia resulted in the creation or reform of binding administrative and judicial organs (Court Chancellery, Aulic Council, Imperial High Court) on the dualistic principle of balance between the emperor and the Imperial Estates. This principle was expressed in the creation of a diplomatic platform known as the Immerwährender Reichstag (Perpetual Diet) a standing congress of envoys supplied by the imperial Estates, which was installed in Regensburg from 1663. Although initiated by Ferdinand’s concessions, the reform of the Empire was not completed until the reign of his successor, Emperor Leopold I.

Within the Habsburg Monarchy things developed in a diametrically opposite direction: Ferdinand emphatically refused to accept any extension of the provisions of the peace agreed at Westphalia to his rights as ruler of the Habsburg patrimonial dominions. He rejected demands for counter-reformatory measures to be abandoned and for the pre-1618 religious status quo to be reinstated in the Habsburg dominions. This would have meant partial toleration of Protestant denominations, the return of emigrants and restitution of confiscated estates in the Austrian and Bohemian lands. It was only in Hungary that Ferdinand was forced to recognize the reality of denominational pluralism.

Nonetheless, in matters of religion Ferdinand III was far more moderate and less fundamentalist than his father. Although the Counter Reformation was continued, it was no longer implemented unconditionally and in such a militant fashion as only a few decades previously. However, the basic situation had changed. Much of the opposition had been broken: the Protestant church structure had been destroyed, the nobility made compliant, the middle classes financially ruined. The consequences of decades of war were plain to see: Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia as well as Lower and Upper Austria north of the Danube had largely been devastated. Religious furore had yielded to disillusionment.

Celebrated as an emperor who had brought about peace, Ferdinand succeeded in having his eldest son Ferdinand IV elected as Roman-German king in 1653. To his father’s great dismay, however, his designated successor died unexpectedly the following year. Efforts to install his next eldest son Leopold in his stead were at first unsuccessful. When Ferdinand died suddenly in 1657 at the age of 49 from an inflammation of the gallbladder, the succession in the Empire was still unresolved.

Ferdinand III was buried in the crypt of the Church of the Capuchin Friars in Vienna. From this time on until the end of the Monarchy in 1918, all the emperors without exception were interred here, in what was to become the principal burial place of the dynasty.