The commitment of Emperor Joseph II to the ‘care of the insane’

Locked up, chained, inspected and observed: this was the fate of the ‘insane’ of Vienna in Joseph II’s tower.

From 1784 the ‘insane’ of Vienna were accommodated in a circular five-storey building. Joseph II, at whose instigation the asylum had been built, thus marked the beginning of the ‘care of the insane’ in Europe. Fully in keeping with the Enlightened reasoning that was typical of this century, in a Court decree of 1781 he laid down who he thought should be detained in the tower, namely:

"Those who cause damage or disgust, … insane persons or those affected by cankers or similar disfigurements, who must be removed from society at large and from the eyes of its people …"

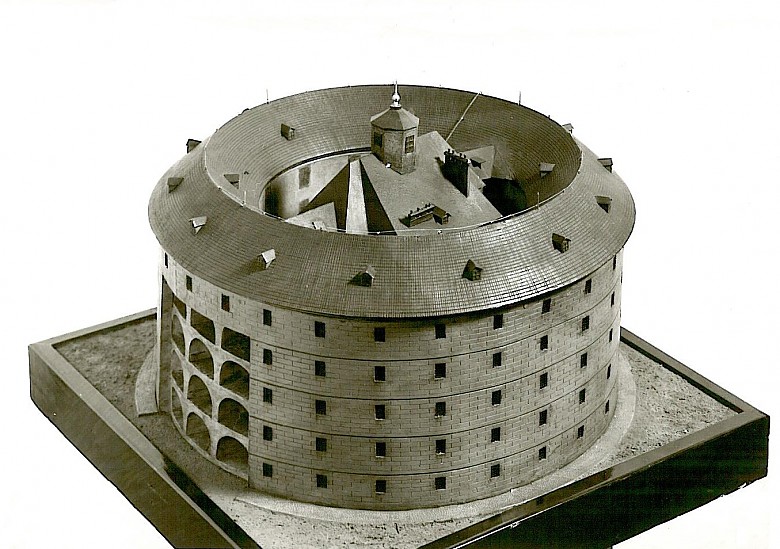

The Narrenturm (‘Idiots’ Tower’), which even today is still jocularly referred to by the Viennese as the Gugelhupf ( a type of tall cake) on account of its distinctive appearance, stood beyond the city walls and at the most remote point within the General Hospital complex. Behind thick doors of wood and steel bars, in small cells, the insane were detained, excluded and separated from society.

The circular architecture of the Narrenturm allowed strict observation of inmates from all sides. The ‘exclusion of irrationality’ was then one of the tasks of the ‘Medical Police’, who were required to provide for public security, since the immediate responsibilities of medicine were not at all clear in the eighteenth century. For this reason the total number of the insane was also small since there was still no pathological or psychiatric expertise in this field. Whether lunatics, beggars or loiterers, they were all included in the group of the ‘poor’. It was only with the building of poor houses, correctional institutions, workhouses, foundling homes and the Narrenturm that there began, step by step, a process of social differentiation. Abnormal and asocial people were supposed to be re-socialized as far as possible, using appropriate measures. Subsequently a distinction was made between ‘curable’ and ‘incurable’ cases of insanity. The incurable remained incarcerated in the Narrenturm.

With all these establishments, institutions and instruments of control, the state sought to gain the most precise information about the population. This central surveillance and social discipline ‘from above’ characterized the enlightened absolutism of Joseph II. It was only in the nineteenth century that the term ‘mental ill’ appeared and with it a new status. The insane person was adopted into medical discourse and became a potentially curable patient.