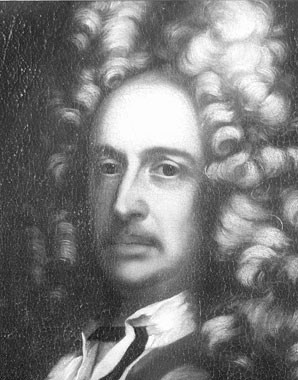

Charles VI, the last Habsburg

Charles VI is regarded as the ‘last Baroque emperor’ and ‘old-school Habsburg’.

Born in Vienna on 1 October 1685, the second son of Emperor Leopold I and his third wife, Eleonore Magdalena of Palatinate-Neuburg, Charles was initially overshadowed by his elder brother Joseph.

Characterized as shy and diffident, with his prominent chin Charles physically resembled his father, conforming to the classic Habsburg type – in contrast to Joseph, who is described as exceptionally good-looking and extrovert in nature.

Ponderousness, an obsession with detail and a pronounced predilection for ceremony and pomp are cited as the defining characteristics of the emperor’s younger son. Often indecisive, Charles held fast to the rigid rules of Spanish court ceremonial that were intended to make the ruler’s person seem remote and far removed from the banalities of everyday life, which suited his withdrawn, reserved character. Intent upon preserving a distance between himself and his courtly surroundings he allowed few people to become close to him. However, he trusted his favourites blindly, making them influential and much-courted but also detested figures at court.

In contrast to his promiscuous brother Joseph, Charles’s marital conduct conformed – at least outwardly – to the Catholic sexual morality demanded by the Viennese court. However, a glance behind the scenes is afforded by the journals in which Charles recorded his daily routine, jotted down in an almost illegible script: here one finds hints of brief affairs with individuals of both sexes.

Charles’s upbringing and education were deeply influenced by the Jesuits, which is said by his biographers to explain his conservative attitudes. Charles was shaped by counter-reformatory Catholicism, and under his rule numerous repressive measures were undertaken by the state against non-Catholics, above all against Protestants and Jews.

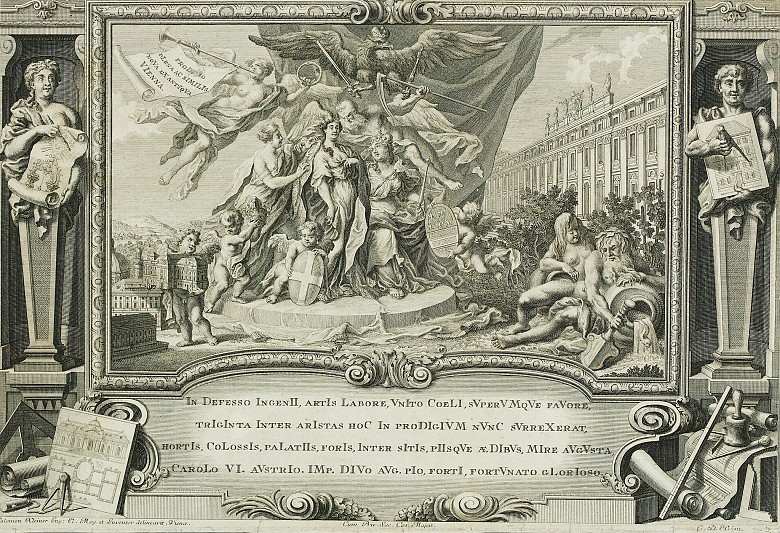

One positive aspect of Charles’s reign can be seen in his keen patronage of the arts. In the field of architecture, where the Viennese court had hitherto failed to keep pace, it made up ground thanks to a number of large-scale projects supervised by court architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach. The Karlskirche in Vienna, dedicated to the emperor’s patron saint, St Charles Borromeo, still attests to the way in which architecture was deployed as a significant propaganda instrument of dynastic and imperial ideology.

Charles also initiated the reorganisation of the imperial collections. His personal interests however lay first and foremost in music. He was himself a gifted musician, and under his aegis the patronage and performance of music at the Viennese court was to reach an impressive standard. Huge sums were expended on concerts, ballets and opera.

Another of the emperor’s passions was hunting, one of the occupations that determined the calendar of the court year. On one occasion, however, this imperial pleasure was clouded by a tragic accident, when Charles accidentally killed a high-ranking courtier, Prince Adam Schwarzenberg.