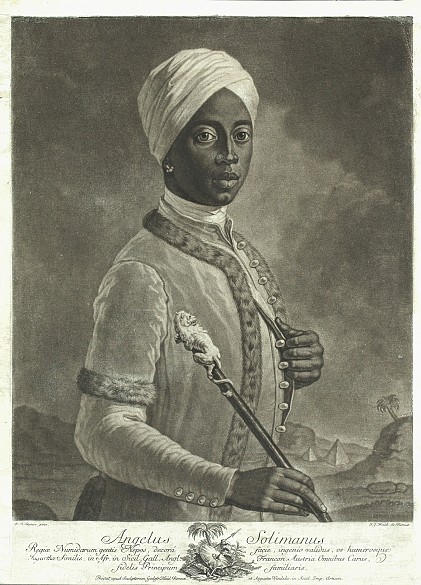

Angelo Soliman

The fate of Angelo Soliman, who achieved considerable fame as a ‘princely Moor’ in eighteenth-century Vienna, is characteristic of the way ‘Enlightened society’ dealt with the exotic or foreign. In Central Europe black-skinned people were regarded as exotic and ornamental accessories on the extravagant stage set that was Rococo fashion.

Soliman was born in Africa around 1720, and was shipped to Europe by slave-traders as a child. He initially worked as a lackey in various aristocratic households, but soon displayed multiple talents and intellectual abilities which won him favour in high society. Soliman spoke several languages and was considered a brilliant chess-player. In 1753 he entered the household of Prince Joseph Wenzel of Liechtenstein.

In the life of Angelo Soliman there were a number of points of contact with the House of Habsburg. In 1760 Soliman accompanied his employer, Prince Liechtenstein, when the latter travelled to Italy as a proxy for Joseph II, escorting Isabella of Parma, the Emperor’s future bride, to Vienna for the wedding. He is therefore portrayed in the painting recording the bride’s entry into the city, a work that is part of a series depicting the wedding celebrations that still hangs at Schönbrunn. He can be seen striding directly beside the Liechtenstein coach, dressed in a strange oriental costume which was probably intended to emphasize his exotic nature and, despite the high social esteem he enjoyed, to present him as a showpiece.

Soliman was also valued by Joseph II as a highly cultured conversational partner. His intimacy with the Emperor subsequently caused him problems when the latter, through an unintentional indiscretion, betrayed to Soliman’s employer his secret marriage to Magdalena von Kellermann in 1768. The prince, who required absolute obedience of his servants, even regarding their private life, did not forgive Soliman his ‘unauthorized act’ and cast him out.

Despite his established position in Viennese society – he was, for example, a member of the Zur Wahren Eintracht Masonic lodge and thus a brother mason of Mozart’s – after his death his body was acquired by Emperor Franz II (I) for the Imperial-Royal Court Cabinet of Natural History. Despite protests from Soliman’s daughter, his corpse was prepared as an exhibit. The subsequent display, in which Soliman’s mortal remains were exhibited to the public, shows clearly how the person of Soliman, valued during his life as an intellectual, was posthumously degraded as a ‘noble savage’: dressed in a loincloth, feathered crown and necklaces of shells, he stood together with three other stuffed black-skinned humans against a screen painted with a tropical landscape, surrounded by exotic stuffed animals.

In 1848 the mortal remains of Angelo Soliman, which had been so ignominiously abused in this way, were destroyed by a fire ensuing from the hostilities during the October uprising.