‘When Adam delved and Eve span …’

In the peasant uprisings of the early modern era, a new interpretation of the Bible was demanded. Feudal overlords exploited the peasants but increasingly neglected the duties that came with their position.

Ever since the late Middle Ages, the ‘divinely ordained order’ of society had been faltering, resulting in open conflict between peasants and their feudal overlords throughout Europe in the early modern era. According to the ‘old’ order, which was based on Roman law, farmers had to give specific amounts of their harvests to the feudal overlords, who in return granted them protection. However, increasing services were being demanded from the peasants: as they had to work longer hours on their lords’ estates in obligatory labour without receiving any remuneration, they were unable to attend to their own smallholdings. They were legally constrained to exclusive use of their overlord’s commercial enterprises, such as mills and inns, and had to buy at particular markets. When a subject died, his overlord exacted 30-40 gulden or, if there was no money, a pair of decent oxen as compensation.

During the Turkish Wars, the precarious situation of the peasants deteriorated even further as their overlords were frequently unable to provide them with sufficient protection.

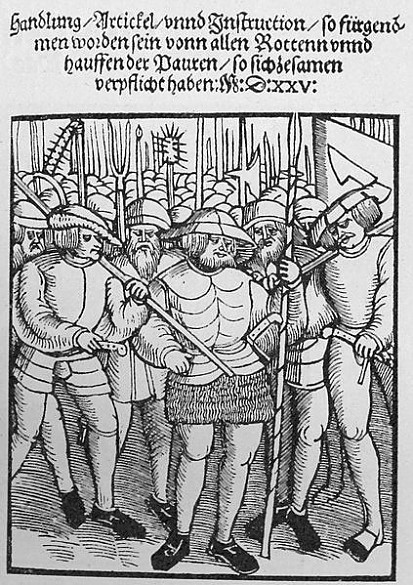

In their uprisings, the peasants first and foremost demanded a reinstatement of their traditional ‘divine’ rights to live a life of dignity and religious devoutness. In support of their demands, many peasants invoked the written word of the Bible, like Luther. Many of them were in fact followers of the Reformation and the Baptist movement and therefore believed in a divine order as stated in the Scriptures. ‘When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?’ went a mocking song. They demanded that the nobility and clergy be abolished as overlords and the peasants put directly under the emperor’s authority. Michael Gaismair, a peasant leader in Tyrol and Salzburg, drafted a constitution for a peasant republic, even going so far as to demand the removal of the territorial ruler – sufficient reason for Ferdinand I to have him thrown into gaol in 1525. The numerous peasants’ uprisings during the sixteenth century throughout the Southern German territory and many of the later Austrian provinces (Salzburg, Tyrol, Carinthia, Styria, Upper and Lower Austria) were all bloodily put down by the superior forces of the imperial army. Trials were followed by public executions to deter further potential revolts.