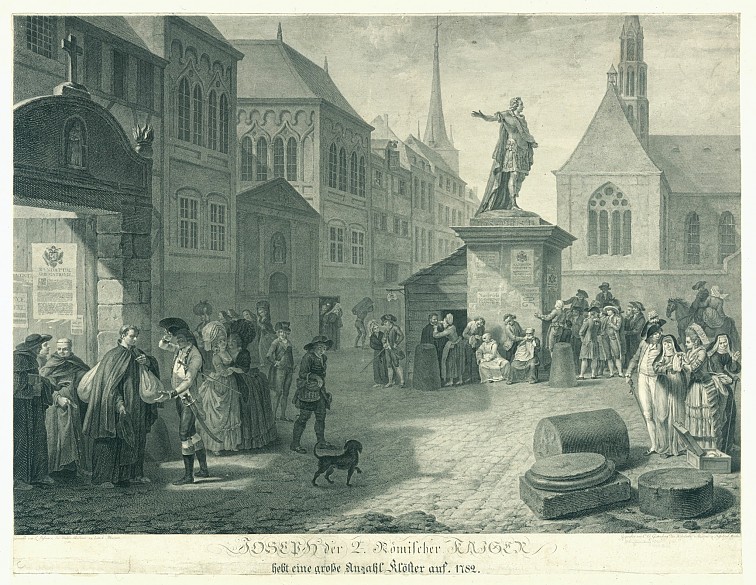

The question of utility: The ‘Klostersturm’ under Joseph II

The ‘great age’ of the Austrian monasteries came to an end with the reforms of Joseph II. His ‘Klostersturm’ or ‘storming of the monasteries’ brought the contemplative life behind monastery walls to an abrupt end. Praying alone was no longer enough.

To say that the network of religious houses in the Habsburg Empire was densely woven is almost an understatement: in 1770 there were 2,163 monastic establishments with more than 45,000 monks and nuns in the territory of the Habsburg Monarchy. Among them were medieval foundations as well as houses established during the Counter-Reformation. Besides the large-scale, rich endowments with their imposing monastic buildings and grounds, there were small and modest religious houses of only local significance.

New standards were applied under Joseph II: in the spirit of the Enlightenment, the question of utility for the common good was now an issue. Only those establishments were to survive that worked in caring for the sick, in education or provided pastoral services in parishes. What mattered to Joseph was whether religious houses brought benefits to the state. Members of religious orders were to transform themselves into ‘more useful and more pious citizens of the state’. Joseph’s reforms therefore aimed to reduce the number of ‘useless’ monks and nuns and increase the ‘useful’ priests, who in reference to their state training were also known as ‘civil servants in a black cassock’.

With the decree dated 12 January 1782, Joseph began dissolving purely contemplative religious houses which ‘had no school, did not care for the sick, did not preach or hear confessions, or distinguish themselves in the schools.’ Initially this often affected women’s convents, since most women’s religious orders obliged the nuns to lead a strictly enclosed life withdrawn from the world, a state contrary to the utilitarian ideal of the Enlightenment.

This was followed a year later by the launching of the so-called ‘Klostersturm’, the second phase of the dissolution, which lasted until 1787. Between 700 and 800 religious houses were dissolved, the buildings either demolished or converted into hospitals, poor houses, barracks and factories.

From the sale of the estates and landed property of the dissolved houses Joseph established the ‘Religion Fund’ of 1782, which financed the salaries of parish priests and curates of the newly set-up parishes. Through this programme of reorganization more than 3,000 new parishes were established. In Vienna three parishes existed in the inner city in 1783 (St Stephen, St Michael and the Schottenpfarre); these were now joined by five others, while in the suburbs (today’s 2nd to 9th municipal districts) there were nineteen parishes. Within the city precincts, there were two members of the clergy for every 1,000 souls, and in the suburbs one priest for every 700 souls. A comprehensive network of parishes was also created in rural districts so that no one would have to walk for more than an hour to get to his or her local church.

Joseph’s plans provided for a further wave of dissolutions in 1791 affecting 450 religious houses. However, they were spared by the emperor’s death.