Good business under the protection of saints – Markets in monasteries and cemeteries

Medieval markets were not only to be found in towns. Markets held in monasteries were thought to enjoy the protection of saints, and there was a very worldly reason for holding them in cemeteries.

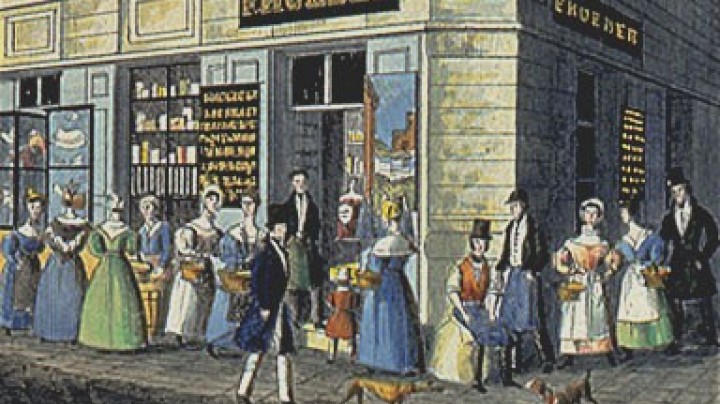

In the Middle Ages markets were sometimes held in what seem to us to be rather unusual places. Since most of them took place on the feast-days of saints, monasteries played an important role. They were places where religious relics were often kept and thus exercised a special attraction for people. And where crowds of people went, traders went too. The link between religious festivals and trade had existed since ancient times. In the early Middle Ages monasteries were given the right to hold markets and fairs in their buildings and on their open spaces. The link between markets and monasteries is clearly shown in the origins of words, especially the German word Messe, which means both ‘mass’ and ‘fair’. In the Middle Ages, in addition to denoting the celebration of the Eucharist, the word was increasingly used to refer to the feast-days of saints, that is to say those occasions when markets and fairs were held. Similarly, the English word ‘fair’ derives from the Late Latin feria, a feast-day.

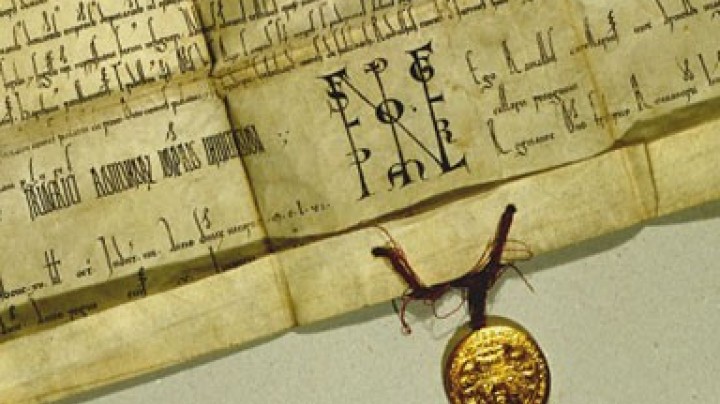

When business was done in monasteries it enjoyed the protection of the saints. This was supposed to give a feeling of security to both traders and customers, helping to protect them, for example, against being robbed. However, contemporaries complained that the fairs held in connection with the feast-days of saints often ended in excessively boisterous celebrations.

What seems unthinkable for us today is that in the Middle Ages it was also possible to hold markets in cemeteries. The advantage of doing so was that the business done there was not subject to the taxes usually levied on markets.