‘It is my will’

An imperial decree turns the capital into a vast construction site. However, the redevelopment was to remain controversial: critics deplored the loss of the old fabric of the city, while modernizers complained that the opportunity to bring radical modernity to this new urban expansion had been wasted.

In 1879 Daniel Spitzer (1835–1893), columnist and satirist in Vienna in the Gründerzeit periodical expressed his views on Vienna’s redevelopment in his Wiener Spaziergänge (Viennese Walks), a column that appeared in the Neue Freie Presse from 1873.Since the new era of construction with its beautification-vandalism has descended upon Vienna, one lingers ever longer in the narrow alleys and gazes up ever more tenderly to the old houses one knows and perhaps will soon never see again. Going for a walk is thus also a continual process of bidding farewell.

On 20 December 1857 a document in the Emperor’s hand was conveyed to the Interior Minister, Baron Alexander von Bach and published in the Wiener Zeitung on 25 December. In it, Emperor Franz Joseph gave the go-ahead for the razing of the city walls and the construction of the Ringstrasse. Like Paris, Vienna was to undergo major remodelling intended to enhance its status as the capital of the Habsburg Empire.

The realization of these plans was the responsibility of the Stadterweiterungskommission (City Expansion Commission): in keeping with the liberal ideas of the time, an open international competition was held and 85 designs submitted. The project that was eventually realized was an amalgam of various designs and was extended and altered during the course of construction. In the design given the Emperor’s personal stamp of approval in 1859 the basic layout of the Ringstrasse was pre-specified: a boulevard measuring 57 metres in width and five kilometres in length, to be lined with monumental public buildings, palaces and private apartment blocks together with squares and parks.

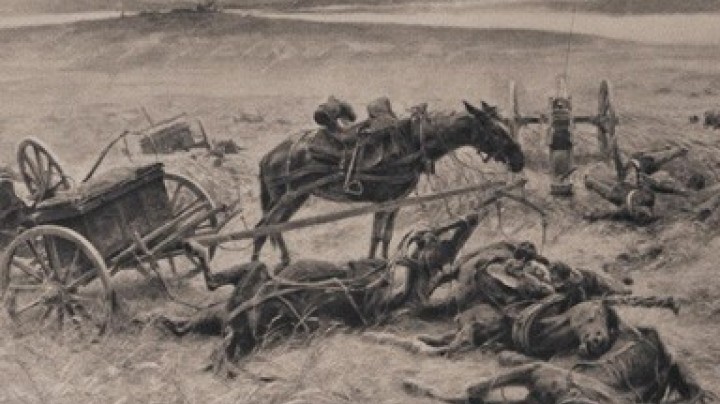

In the following years Vienna was gripped by a frenzy of demolition and construction, as immortalized by Johann Strauss in his Demolition Polka.

The cityscape of Vienna changed daily, and whole streets in the vicinity of the Ringstrasse and the old city centre were rebuilt. Old houses were torn down. The destruction provoked criticism and was described as ‘barbarism’, ‘beautification-vandalism’ and ‘speculation’. Painters and photographers recorded the old buildings before they were demolished. Those intent on preserving the city’s heritage issued an appeal to ‘save Old Vienna’. Even theoreticians of urban planning such as Camillo Sitte criticized what they saw as the ‘drawing-board city’.

A number of architects regarded the Ringstrasse in retrospect as badly planned and demanded that the city be redeveloped not on the basis of the greatest maximum profit but as a realization of socio-political and urbanist ideas. In his study of 1911 entitled Die Großstadt (The Metropolis), Otto Wagner (1841–1918) for example developed the concept of a functional, ‘hygienic’ city with as regular a layout as possible. Adolf Loos (1870–1933) saw the Ringstrasse as Vienna’s central problem: a vehement opponent of Historicism, in his Plan von Wien (Plan of Vienna) of 1912/13 he sketched out a radically altered urban space with new visual axes and monumental plazas.