Living in a top location – Neighbours of the Habsburgs

The Habsburgs thought that members of the aristocracy and the prosperous bourgeoisie, who would bask in the splendour of the imperial dynasty, would make desirable neighbours.

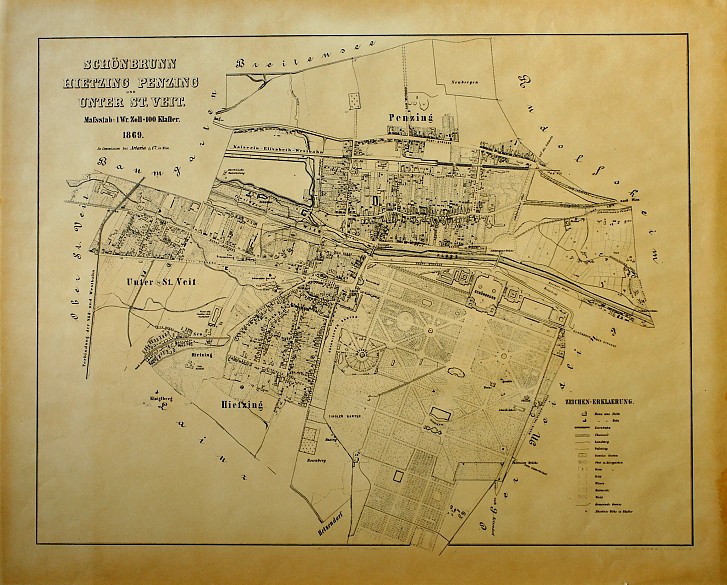

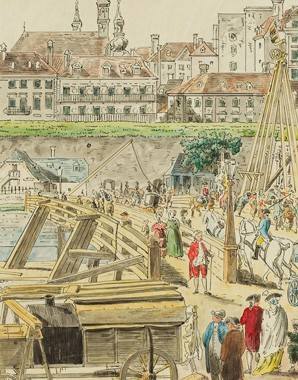

The imperial Court was situated in the centre of Vienna, while Schönbrunn Palace lay just outside the city. Both locations had a magnetic effect on some sections of the population of Vienna and hence they had an impact on the city’s appearance. The Habsburgs’ neighbours were the aristocracy and the upper middle-class, the latter building magnificent palaces along the Ringstrasse boulevard and on greenfield sites in the outer suburbs in order to be near the places where the imperial family resided. In the inner city (now the first district of Vienna), which was surrounded by walls until 1857, houses were built with spacious apartments which were expensive and could be afforded only by, for example, wealthy entrepreneurs. These expensive apartments were also lived in by high-ranking civil servants, whose social status meant that they were expected to reside near the imperial Court and in a manner in keeping with their station, especially as the seats of government and administration were located near the Imperial Palace. In the midst of these rich inner-city residents craftsmen specializing in luxury goods set up their businesses, since they hoped that the proximity of the Court and the presence of the rich upper-middle class would provide a good market for their products.

There was no place in the exclusive inner city for workers, small traders and businessmen and the lower social classes, even though they made up a large part of the population of Vienna. Small traders such as cobblers or tailors established themselves above all in the inner ring of suburbs, and their houses were where they lived, worked and sold their goods. Most workers lived still further away from the centre of Vienna; for financial reaons most of them lived in the outer suburbs beyond the Linienwall, a rampart built around the inner ring of suburbs. They could only afford to pay as little as possible for accommodation and food and thus lived in the suburbs in small apartments in tenement blocks, cramped quarters where rents were relatively low, in places where the city’s consumption tax was not levied. After the second enlargement of Vienna in 1890-2 and the inclusion of the outer suburbs in the municipal area it was thus these districts that had the highest population growth rates. In the nineteenth century there was a close connection between where people lived and where they worked, the result of numerous factories being set up in the outer suburbs and alongside railway lines because land prices there were relatively low and goods could be transported cheaply by means of the railway. Moreover, the workers who lived there were hardly likely to complain about the noise and odours emanating from the factories. On the other hand, the middle classes saw the arrival of large numbers of workers as a devaluation of ‘their’ former recreational areas. Similarly, wealthy upper middle-class people lived near Schönbrunn Palace, spending the summer there in their spacious country houses and villas.