Joseph II as viewed by posterity

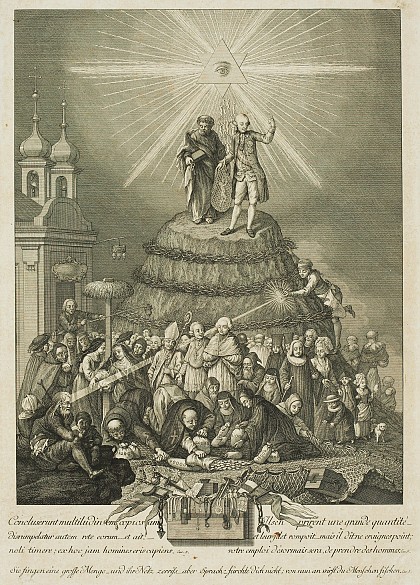

Evaluation of Joseph II and his reforms has always been divided. Even during his own lifetime he encountered fierce opposition from traditional elites. However, representatives of the Enlightenment saw in him the hope of a better society.

The initial popularity of the young co-regent, in whom great hopes were placed by many across Europe, dwindled as he proceeded with his radical measures for reform. At his death his work lay in ruins, and his tragic failure became apparent.

However, faced with the repressive measures implemented by the Austrian government to counter the ideas that were being disseminated across Europe by the French Revolution, the following generations began to see his achievements in an increasingly positive light. A veritable cult for erecting monuments in his honour developed. The most important of these was unveiled on the Josefsplatz in Vienna in 1807.

The subsequent reintroduction of censorship forbidding any free expression of opinion strangled the lively press and flourishing literary production of the Josephinian era. The powerful bureaucracy and the authoritarian measures depriving of the people of their right of decision – although introduced in their basic form by Joseph himself – mutated into the police state of Metternich under Joseph’s nephew Franz II (I).

The liberal ideal of a state church, which resulted in the strict control of the Church by the state, remained in force until the reign of Franz Joseph and the Concordat of 1855. It would take a long and arduous struggle before Church influence on family law and schooling was once again eliminated.

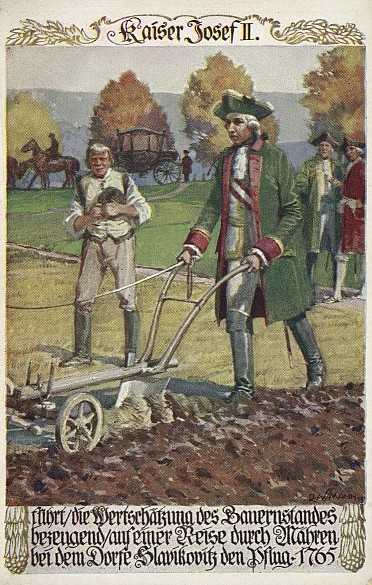

The only one of Joseph’s reforms to remain was the abolition of serfdom. In this Joseph indeed earned his reputation as the venerated ‘emperor of the people’. This is attested by the wide distribution of the print depicting the emperor ploughing. On one of his journeys across Moravia in 1765 the emperor ploughed a stretch of field near Brünn (Brno) as a sign of his close attachment to the peasantry. It was a successful public relations measure that made him the idol of the peasant classes.

Joseph was also invoked by the German Nationalist movement during the time of the nationality conflicts in the multi-ethnic empire. In the Josephinian era’s tendency towards centralism that went hand in hand with promoting the role of German language and culture they believed to have found ideological support for their demands for the primacy of Germanity in the Monarchy.

Other institutions that saw a model in the figure of the reformist emperor were the civil service and the army. Joseph always served as a figure of reference in demands for a centralized and regimented apparatus of state and army. Here Joseph was glorified and the despotic features of his reforms disregarded.