First meeting and wedding in Paris

On 13th March 1810 Marie Louise set off with a great retinue of coaches towards an uncertain future.

At first her Austrian entourage was allowed to accompany her, but once she reached the Bavarian border her last confidantes were forced to leave her. "I assure you, dearest Papa, that I am truly unhappy and cannot console myself," she wrote to her father after the handover in Braunau. Yet the longer the journey went on, the better Marie Louise felt. Napoleon, who was an expert at seducing young women, sent her frequent love letters and presents, and she soon began to develop sympathetic feelings towards him. Napoleon himself was waiting impatiently for his bride in Compiègne, and when, after 14 days, she and her retinue finally neared the city he spontaneously rode out to meet them. He met the column as they changed horses at a post station and without further ado joined her in her carriage. Once she had recovered from her initial shock Marie Louise was impressed by her husband's handsome appearance. Napoleon decided to cancel the arranged ceremony of welcome and to travel immediately to Compiègne with his bride, where he – in a complete breach of normal protocol – made her his wife that very night.

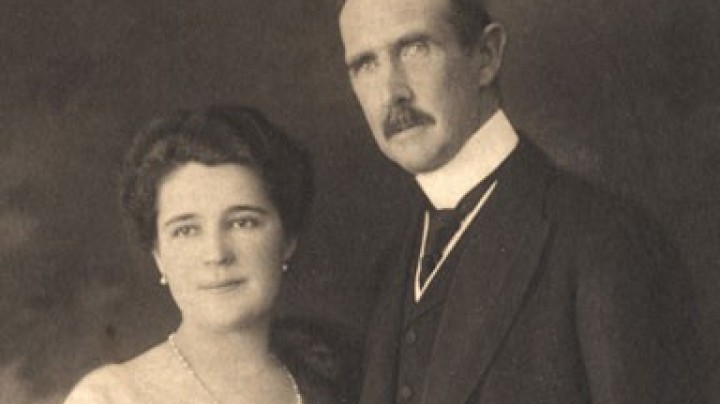

Napoleon's reputation as an excellent lover was obviously deserved when it came to Marie Louise. In the first letter she wrote to her father after the early wedding she said that all the doubt that she had felt just a short time before had been replaced with euphoria: Napoleon loved her dearly and she returned his love, wrote an obviously happy young wife. Just two days later the couple travelled from Compiègne to St. Cloud, where the civil ceremony took place. From here they continued on to Paris, setting off in glorious weather on 2nd April 1810 in a procession of 50 luxurious carriages and 240 horsemen. The Imperial couple rode through lines of guards and cheering crowds along the Champs Elysées to the Louvre, where Cardinal Fesch presided over the final church wedding.

However, a significant incident cast a shadow over the dazzling event: of the 29 cardinals resident in Paris only 10 attended the wedding. The prominently placed empty seats were an obvious indication that they doubted the validity of the marriage, since the Pope had not declared Napoleon's first marriage invalid. This passive resistance threw the Emperor into a disproportionate rage: he saw it as a strategy designed to deny the right of inheritance to any future heir. For the deeply religious Marie Louise this was probably the first time that she realised that from the Catholic point of view her marriage was far from unassailable.