A year at Court – the Court Calendar

For the old Austrian aristocracy the imperial Court was not only the centre of its existence; the rhythm of their lives was determined by the strict rules of the Habsburg Court.

The Court year began with the Neujahrscour (New Year’s reception) at Court. The nobility of the empire appeared at the Hofburg in order to pay their respects to the emperor and to convey their seasonal felicitations to the imperial family. This took place in accordance with an elaborate procedure that revealed the fine hierarchical nuances characterising life at Court. Only the diplomatic corps, members of ruling families and those members of the aristocracy who held the most senior honorary posts at Court were permitted to attend upon the emperor in person. The other members of the aristocracy who were admitted at Court had to make do with the Obersthofmeister (head of the emperor’s Court household) as the monarch’s representative, who then relayed their felicitations to the emperor.

An analogous procedure took place with the ladies at Court: the wives of the ambassadors and senior Court officials were received by the empress in person, while the other aristocratic ladies had to present themselves to the head of the empress’s Court household.

The reception marked the opening of the social season and the beginning of a whirl of balls, masked festivities and other entertainments. The highlights of the season were the two balls at Court. The first to take place was the Court Ball: this was equivalent to the state ball of the monarchy, to which 2,000 guests from Viennese high society were invited. Besides the aristocratic elite the guests also included individuals from political and economic life as well as high-ranking army officers. Two weeks later the ‘first tier’ of society met at the ‘Ball at Court’, a more exclusive event that was reserved for the aristocracy who were admitted at Court. This was the absolute climax of the social season and could only be attended on the personal invitation of the emperor.

The ball season and the boisterous carnival celebrations ended abruptly on Ash Wednesday. During Lent no dances were held, but concerts and soirees were permitted. A round of ecclesiastical feast days began which likewise constituted an important element of Court social life. The social season in Vienna ended with the Corpus Christi procession, which was a visible demonstration of the traditionally close link between throne and altar, and at which all members of Court society presented themselves in accordance with their rank and name.

In summer most of the Viennese nobility left the city for their country estates. It was the time of the summer retreat, of relaxation and the pursuit of individual interests, punctuated by visits to the estates of neighbouring aristocratic families.

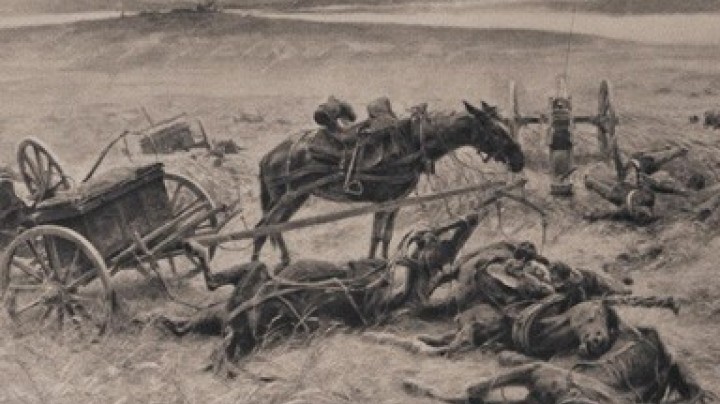

Autumn was dominated by the hunting and shooting season, traditionally claimed by the nobility as a feudal privilege and regarded as a sport befitting their social status. Families who owned suitable tracts of forest invited others to large shooting parties which served to reinforce the feeling of aristocratic solidarity.

Soon after Christmas life returned once again to the Viennese palaces of the nobility and the round of social events began anew.