Otto, the last ‘crown prince’

Otto made his first public appearance as a representative of the House of Habsburg at the tender age of four, at the funeral of his great-great-uncle Emperor Franz Joseph in November 1916.

The funeral procession was an impressive spectacle and remained engraved on the memory of many participants and onlookers. The young Otto walked behind the catafalque wearing a brilliant white tunic with a black sash which stood out against the sombre procession. As a symbol of innocence and new beginnings he attracted the sympathy of the crowd in a time of war-weariness and lack of hope. The child’s presence was a public relations coup, given that the dynasty no longer enjoyed undivided support after the death of the aged emperor.

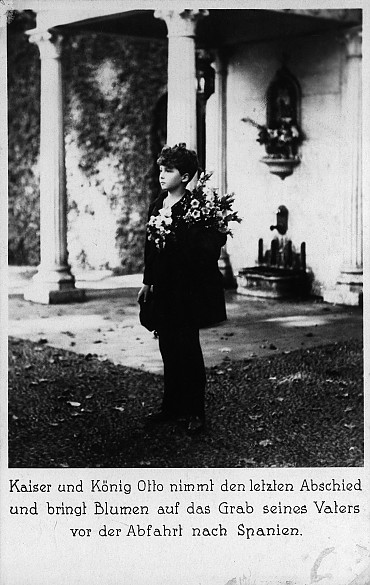

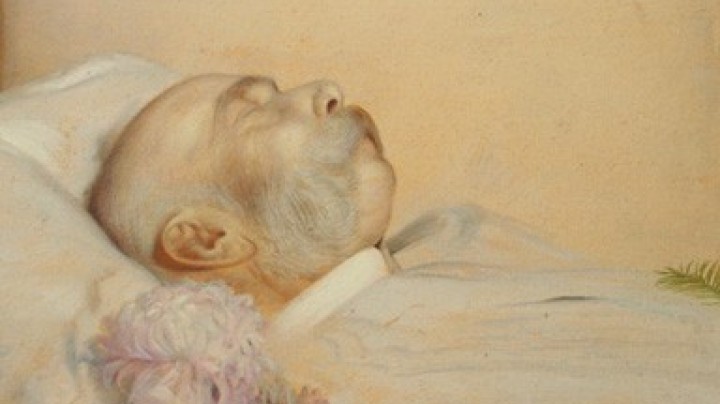

As a child Otto experienced the fruitless efforts of his parents to regain the power they had lost. Aged nine he witnessed his father’s death agony: Karl insisted that his son be present so that he could see ‘how a Christian returns to his Creator’.

As he was the eldest son, Otto was groomed to be his father’s successor after the latter’s early death. From his earliest years he was brought up as the future head of the dynasty who might one day regain the throne. Thus immediately after his father’s death Otto was addressed as Imperial Majesty, and those around him had to accord him every obeisance due to an emperor, despite the straitened circumstances they were living in. When Otto attained his majority in 1930, his mother put the political legacy of his father into his hands and he was formally recognized as the head of the dynasty.

This claim was also reflected in his education: taught at first by private tutors, for the last few years of his schooling he attended the secondary school run by the Benedictine Abbey at Clairvaux in Luxemburg. Even his school leaving exams were co-opted as a declaration of his status: the former emperor’s son was examined by a panel of Austrian and Hungarian teachers in accordance with the regulations that had pertained before 1918.

After this he began to study law and political science at the University of Leuven in Belgium, where he was matriculated under the pseudonym ‘Count of Bar’. The latter was one of the titles borne by the head of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty, and was also a clear reference to his Lotharingian roots.

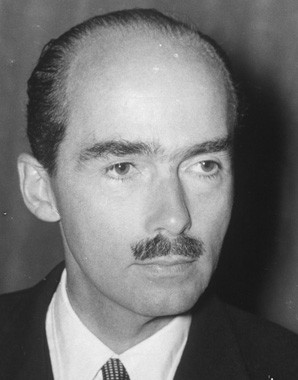

While spending a term studying in Berlin in 1932/33 he witnessed the National Socialist takeover of power on 31 January 1933 and left Germany immediately. In 1935 he completed his studies and received his doctorate in law. In 1936 he began to be active in the Pan-Europa movement. This had been founded by the Bohemian aristocrat Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi with the aim of uniting Europe on the principles of democracy and Christian ideals as a counterweight to the totalitarian tendencies of the chauvinist-nationalist and Communist factions.

In the meantime the political climate in Austria had changed, and public opinion – at least in Conservative-Catholic circles – increasingly began to see positive sides to the Habsburg legacy. Otto won support from the ‘Iron Ring’ monarchist association which became a platform for the hitherto unorganized legitimist tendencies.

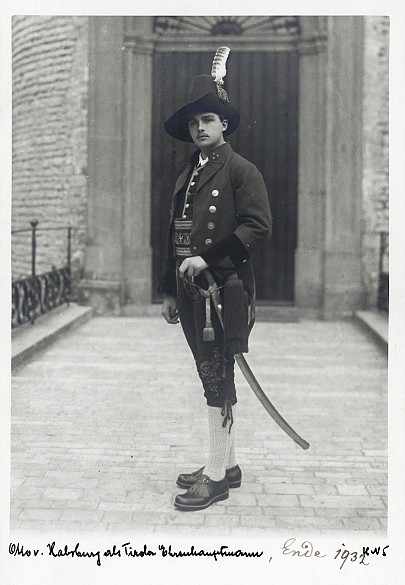

In 1931 Otto was made a freeman of the town of Ampass in Tyrol. This was the first sign of a changed attitude towards the dynasty. This initiative gradually became a veritable movement; by 1938 Otto had been made a freeman of 1,603 towns in Austria.