Turquerie – the reception of the Orient in Europe

Desired, feared and romanticized – the reception of the Orient in the Occident varies according to historical circumstance between attitudes of rejection and appropriation.

Turquerie or the fashion for all things Turkish denotes the European interest in the Orient, particularly the culture of the Ottoman empire, and its influence on art and culture from the sixteenth century onwards. It was – and is – primarily not so much concerned with the real circumstances pertaining in these countries but rather a product of European fantasies about the fabled luxury of Oriental cultures; Turkey was familiar as a supplier of luxury goods such as spices, perfumes, coffee and tea.

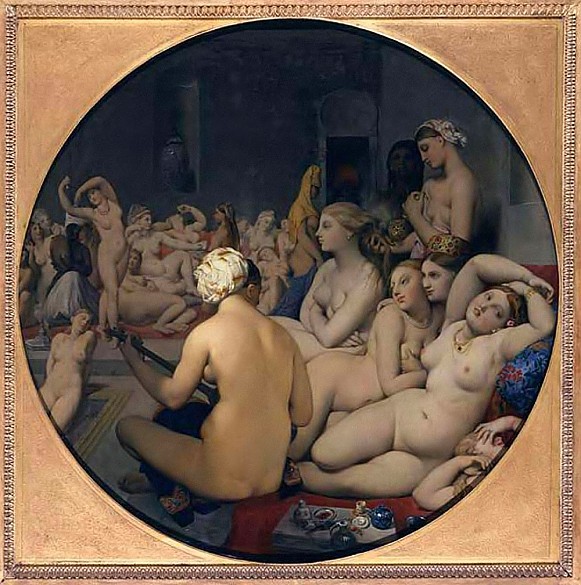

Fantasies of the Orient as a locus of the ‘Other’, of the exotic and decadent, culminated in the nineteenth-century depictions of the harem as a place of female erotic sexuality from which men were barred. All these ideas manifested themselves in many genres of art as well as in aspects of courtly – and later upper-middle-class – daily life, such as dress, fabrics, interiors and porcelain. This fantasy of the Orient as a place of luxury and riches provided Europeans with opportunities for self-expression and differentiation.

The long-lived Turkish fashion was fuelled from a broad spectrum of images ranging from the barbaric foe of the West and the brave warrior to the cultivated, even erotic exotic figure. Writers and philosophers used the Orient as a screen onto which they could project critiques of their own societies and designs for better ones.

These images shifted and changed with the prevailing political and cultural situation and were instrumentalized accordingly: under the influence of the Enlightenment, the ‘Oriental’ was invested with qualities such as goodness, tolerance and strength of faith, a famous example being the characters in Mozart’s opera The Abduction from the Seraglio. In previous centuries, when the Turks had represented a real danger to certain European countries, the reception of Oriental culture swung between fear and admiration. This opposition underlay ‘practices’ such as tournaments in which military victories over the Turks and Christendom over Islam were ‘performed’. A popular pastime both at court and in lower middle-class and peasant circles was Türkenkopfstechen, which involved impaling wooden figures or heads of Turks from the back of a galloping horse.