Revolution! Academic freedom for the university and women in the lecture halls

The students continued to uphold their reputation for unruliness in the nineteenth century, revolting against the authorities and the unacceptable conditions that prevailed at the university. Women were not permitted to study until 1897.

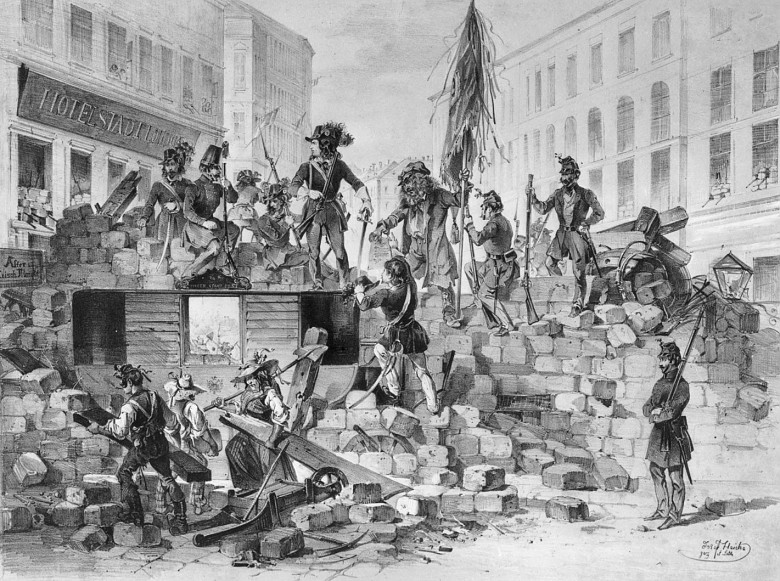

The quality and standing of Vienna University had deteriorated during the reign of Emperor Franz II (I). Both the students and some of the teaching staff were dissatisfied with the political system and in particular with prevailing conditions at the university. Many took an active role in the revolution of 1848, occupying the university quarter and erecting barricades in the streets. After the violent suppression of the revolt by the imperial army the university was closed down for a year.

However, the rebel students did achieve one of their aims: the principle of academic freedom for teachers and students was incorporated in the university statutes of the nineteenth century, statutes that today still form the basis of the university constitution. The faculty of philosophy was reorganized as an institution of research and teaching. The principle of academic freedom was enshrined in the constitution of 1867 – even if the history of the university, both under the Habsburgs as well as more recently, particularly during the National Socialist era – has sometimes demonstrated a lamentable failure to uphold it.

Women were long excluded from university education. In 1878 they were admitted as auditors, that is to say they could attend and listen to lectures. With the demand for civil rights for women, representatives of the women’s movement campaigned for them to be admitted to university. For a long time debates about their physical and mental suitability had hindered their admittance. In order to be able to study at university in Austria, students had to have obtained their school-leaving diploma (Matura), but the legal basis for women to acquire this diploma was not created until 1896. It was thus 1897 before women were admitted as students at the faculty of philosophy in Vienna – more than thirty years after they had been admitted to the University of Zurich. From 1900 they could enrol to study medicine, and the other faculties gradually opened their doors to women over the course of the twentieth century. The first woman to obtain a doctorate in Austria was Gabriele Possanner von Ehrenthal (1860–1940), in 1897.